“A black male neurosurgery applicant… I’ve never seen that before!” The comment was publicly directed towards me, delivered across a table where I sat with a dozen other applicants at an interview dinner in 2013. I was shocked, humiliated and angry. My shock came from the audacity of the white, male, senior neurosurgery resident who made the comment. Smiling in spite of my internal state, as I searched for an appropriate reply, was humiliating. The many dimensions of social injustice that enabled a neurosurgeon in-training to address me this way – despite having a U.S. president in office who at least symbolically exemplified a historical victory against anti-black racism – made me angry.

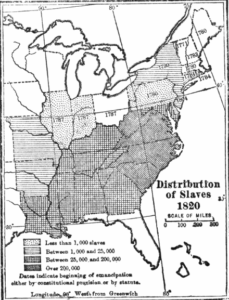

Neurosurgery will fail to transform into an innovative medico-surgical subspecialty unless we are willing to acknowledge that currently, our field is structurally racist, and therefore sorely lacking in its modernity. Structural racism refers not only to the minority of our colleagues who openly express anti-black racism but also to the power structures of neurosurgery that are founded upon racist ideas and history. The steep hierarchical structure of academic neurosurgery virtually immortalizes race-based processes that American society has inherited from the colonial legacy, and the immense generational wealth created for white Americans through systematic enslavement and exploitation of some 388,000 black Africans imported into North America between 1560 and 1850 (Figure 1). [1]

The privileges of white race, and the disadvantages of under-represented minorities (URM) racial categories, have well-documented impacts on the aspiring neurosurgeon, powerfully influencing the odds of every major experience/variable affecting applicant candidacy for neurosurgery residency. [2,3] Success in neurosurgery is consequently strongly rooted in the ability of aspiring neurosurgeons to emulate white American males, while keeping non-whites out of this medical profession. Harvey Cushing exemplified this racist precedent in many cited instances of his own racism such as his opposition to hiring black nurses in municipal hospitals, with a message to Cleveland’s director of public health stating, “I am sure that colored women would often make excellent trained nurses… But this will mean that colored men who are their friends… will have to appear at the nurses’ parties and receptions and this would be absolutely disastrous to the whole social status of your training school.” Another example comes from Cushing’s letter to his mother about a gorilla in the laboratory of Charles Sherrington: “…Coal-black — I don’t believe you could have distinguished his ear from a darkies [sic]. He smelled just like a dirty Negro — behaved like one.” [4]

Racial background, therefore, influences every apparently objective measure of merit used to select candidates for neurosurgery training including board exam scores, research opportunities, quantity/quality of publications, and quality/source of recommendation letters. [5,6] Indeed, black applicants predictably encounter greater challenges than their white counterparts in medical school admissions, academic performance, successfully matching into a neurosurgery residency, and succeeding as attending neurosurgeons. [5,6] The recognition of these barriers by many black applicants, and the systematic ignorance of these barriers by neurosurgery’s leaders and decision makers, serves to perpetuate structural racism in neurosurgery, while contributing to the destructive psychosocial burden carried by neurosurgery applicants, trainees and practitioners from URM groups.

Patient experiences in neurosurgery also reveal the racism of neurosurgery’s eco-system. A recent correspondence in the New England Journal of Medicine exposes the racially segregating practice of sending patients from distinct socioeconomic strata into two different kinds of outpatient experiences: public “resident” clinics for patients with racial backgrounds that predominate among the uninsured or Medicaid subscribers, and private “attending” clinics where one more easily encounters white patients with “good” insurance. [7] Having personally witnessed this phenomenon in neurosurgery, I suspect it is a familiar pattern for most neurosurgeons.

Racial background similarly influences patient outcomes in the neurosurgery’s eco-system. Patients from URM groups tend to be at higher risk of poorer outcomes across neurosurgical pathologies, iatrogenic complications, and unfavorable disposition after treatment due to factors such as insurance status, access to rehabilitation services, cost of medication, health literacy, and other social determinants of health. [8–12] The strides made by people of URM backgrounds in neurosurgery, despite the harsh realities of structural racism, must be acknowledged and celebrated, however they also serve as reminders that such accomplishments remain exceptions to rules that normalize the abnormal context of racial injustice. Until the neurosurgery profession embraces a fully anti-racist approach to advancement, we will fail to transform our profession into an authentically evolved medico-surgical enterprise. [3]

Figure 1 Source: Johnson, Allen (1915). Union and Democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company. In the US public domain.

References:

1. The National Park Service. The Middle Passage. https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-middle-passage.htm. Published 2021. Accessed October 15, 2021.

2. Myser C. Differences from somewhere: The normativity of whiteness in bioethics in the united states. Am J Bioeth. 2003;3(2):1-11. doi:10.1162/152651603766436072

3. Detchou DK, Onyewuenyi A, Reddy V, et al. Letter: A Call to Action: Increasing Black Representation in Neurological Surgery. Neurosurgery. 2021;88(5):E469-E473. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyab057

4. Agin D. Bigotry and Racism in America: What Harvey Left Us. The Huffington Post Blog. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/bigotry-and-racism-in-ame_b_241080/amp. Published 2009.

5. Edmond MB, Deschenes JL, Eckler M, Wenzel RP. Racial Bias in Using USMLE Step 1 Scores to Grant Internal Medicine Residency Interviews. Acad Med. 2001;76(12):1253-1256. doi:10.1097/00001888-200112000-00021

6. Gardner AK, Cavanaugh KJ, Willis RE, Dunkin BJ. Can Better Selection Tools Help Us Achieve Our Diversity Goals in Postgraduate Medical Education? Comparing Use of USMLE Step 1 Scores and Situational Judgment Tests at 7 Surgical Residencies. Acad Med. 2020:751-757. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003092

7. Vinekar K. Pathology of Racism — A Call to Desegregate Teaching Hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(13):e40. doi:10.1056/nejmpv2113508

8. Thomas G, Almeida ND, Mast G, et al. Racial Disparities Affecting Postoperative Outcomes After Brain Tumor Resection. World Neurosurg. August 2021. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2021.08.112

9. Kittner SJ, Sekar P, Comeau ME, et al. Ethnic and Racial Variation in Intracerebral Hemorrhage Risk Factors and Risk Fa ctor Burden. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2121921-e2121921. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21921

10. Mehta AM, Fifi JT, Shoirah H, et al. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in the use and outcomes of endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke. Am J Neuroradiol. 2021;42(9):1576-1583. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A7217

11. Elsamadicy AA, Freedman I, Koo AB, et al. Impact of Racial Disparities on All-Cause Mortality in Patients With Tumors of the Spinal Cord or Spinal Meninges: A Propensity-Score Analysis. Glob Spine J. July 2021. doi:10.1177/21925682211033827

12. Asemota AO, Haider AH, Schneider EB, George BP, Cumpsty-Fowler CJ. Race and Insurance Disparities in Discharge to Rehabilitation for Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30(24):2057-2065. doi:10.1089/neu.2013.3091