Wally was surrendered to the Tulsa Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) at the age of five. He was a blind shih-tzu mix with a bad haircut, making his adoption fee heavily discounted. He was incredibly smart, but quietly stubborn; well behaved, but always playful. In the years that followed, he remained by my side as I moved to a new city, weathered through medical school and traveled across the country convincing residency programs that I was deserving of my dream career. He wasn’t much of a dog’s dog, but he had an unconditional love for tennis balls and me. As an immigrant navigating life in the US without my family, I relied on him as my constant. He was my world.

I’ve been through many transitions in life, but there was nothing quite like the transition into neurosurgery residency. Treating people whose livelihood drastically changed overnight has a way of changing your outlook. I constantly questioned whether I was doing enough to leave this world with no regrets. Wouldn’t it be nice, I thought, if I could give many more Wally’s a good home? However, the idea was consistently shot down by some version of not having enough time, skills or money.

Towards the end of my intern year, Wally no longer had a bad haircut, but he had acquired congestive heart failure. As we frequented the veterinary ICU, my excuses were overpowered by a simple question: “if not now, then when?” Someone said to me that losing a pet leaves a hole in your heart, and that hole never closes, just gets smaller over time. The day Wally left this earth, that hole felt infinite.

Generously named by the region’s existing animal rescue, Sujijantarat Animal Sanctuary (SAS) was opened in Kanchanaburi, Thailand, a few months after Wally’s passing. I addressed my first two excuses – not enough time and skills – by leveraging my local friends and family as volunteers, and by making the decision that the shelter would be managed best by an existing rescue who already had operational experience, but was in dire need of a more sanitary living space. I addressed the last excuse – not enough money – by simply calling my own bluff. Anyone who has been to a developing country knows that US dollars stretch far more there than you could imagine. I know this because I was born and raised in Thailand, where one month’s worth of food for one dog costs $9. Almost five years later, what started as an attempt to fill a hole in my heart, is now a sanctuary to more than 300 Wally’s and the largest no-kill, small-animal shelter in the region.

By all accounts, SAS was born from a shoot-first, aim-later approach. This may seem contrary to everything you were taught in neurosurgery, a field in which you are accustomed to analyzing something thoroughly before committing to an action. I would argue, however, that outside of the operating room, achieving something truly fulfilling requires that you first commit yourself to seeing it through. Why else, then, would you commit to 15 years of sleepless nights, before you know with certainty if a particular career would be worth it? My hope for this story, is that if there is something lurking in your heart, something you know would be immensely meaningful to you and your community, that you realize that as a neurosurgeon, you have the power and the leverage to create a lasting change.

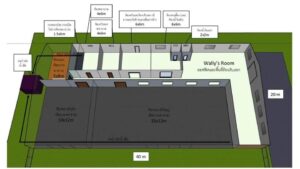

Below: the SAS during different stages of development.

To learn more about SAS, the work we do, and how you can help, please visit www.sasthailand.com or follow us on Instagram at @sas_thailand for more information.