“Since George Floyd’s violent death last year, many academic medical centers have begun addressing systemic racial problems. Many have formed committees to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion, almost always making sure to include minority students, fellows, and faculty in those efforts.

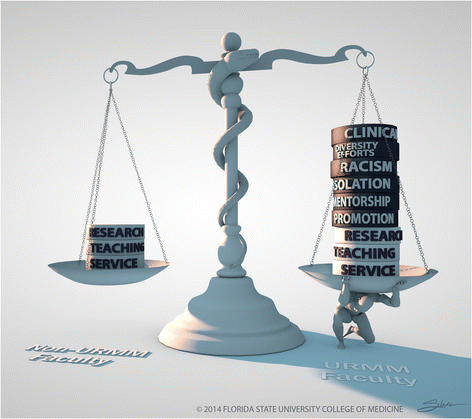

But these diversity initiatives are often a double-edged sword for minority faculty. To pursue an antiracist mission, institutions call on Black and Brown faculty for help. Although such service is meaningful and important, it is not always compatible with traditional metrics of academic success. The overtime spent on diversity initiatives comes at a cost for minority faculty — a toll known as the minority tax.” (Williamson 2020).1

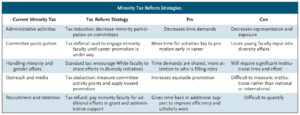

This is an excerpt from a recent perspective article written in the New England Journal of Medicine suggesting strategies to reduce taxation and improve promotion and retention of faculty of color.

This is an excerpt from a recent perspective article written in the New England Journal of Medicine suggesting strategies to reduce taxation and improve promotion and retention of faculty of color.

Dr. Scott Porter is an orthopedic surgeon who specializes in oncology at the University of South Carolina in Greenville. He is a leader in his field, a social entrepreneur and the vice president of culture and inclusivity in the Greenville Health System. He is an African American man who on his path to leadership, constantly considered the role of the minority tax both for himself and for those in the organizations he leads.

As a neurosurgeon and author of Minority Tax Reform, I had the privilege of asking him about his experience.

What do you think of the minority tax?

“The minority tax is an interesting concept that in and of itself is a double edged sword. On the one hand, there has been enough progression in the professional space to have minorities in certain positions of pseudo power or even power that allow for there to be someone to answer questions that majority populations may have. On the other hand, the numbers have been so few that it necessarily invites the opportunity for people to think that this one successful person is in a position to speak for the masses.”

How have you seen the minority tax play out in your experience?

“Often, individuals wish for minorities, particularly Blacks, to speak for an entire community. Take as an example affirmative action versus nepotism. If one dares to speak of the ills of nepotism, society only assigns those ills to the recipient of the nepotistic hiring, matriculation or matching in the case of medical education. Rarely does society condemn all successful people with children even when nepotism is rampant – and as an aside, we won’t bring up the college scandal from a few years ago. In the case of perceived affirmative action, in contrast, the entire institution of affirmative-action and nearly every professional that is a member of the recipient diversity class gets persecuted. I think that there is a natural predisposition for majorities to think that a minority speaks for all minorities. Perhaps it is a numbers game in that there are so few Blacks in positions of authority that when identified, members of majority diversity dimensions seize upon the opportunity to address burning questions. Equally feasible however is an absence of awareness of being the perennial and never-ending spokesperson for a very heterogeneous population of 45 million individuals.”

How can we help with the minority tax?

“We as a society increasingly find the mental weight of open debate, of balancing an amazingly complex 24/7 instant information cycle, of increasingly polar thought processes, etc., to be so burdensome that our populace rightfully needs all the sundry mental health treatments to simply cope. On this backdrop, there is surprisingly little attention paid to the mental weight that is experienced on a daily basis by minority professionals – and specifically Black professionals – as they attempt to balance the desire to quietly blend into the dominant culture as colleagues or employees while being seen by many in that culture as some type of spokesperson for nearly every newsworthy social event.”

What is your experience of recruitment and promotion and how can we make it better for faculty of color?

“My experience represents a single individual. It would be interesting if we could catalog our experiences and note any similarities. Most of the time, the recruitment and promotion experience is one that is largely objective. That being stated, the data on the diversity or lack thereof as one ascends the academic ladder is what it is.”

“What is most striking to me is the seemingly pervasive belief that minorities somehow need something different than majority individuals to be recruited. Safety, respect, value, opportunity… these are all things that individuals want regardless of their racial, gender, religious backgrounds. It seems that when we interview majority people, the environment provides many of these things inherently and therefore we have no impetus to look for reasons to either point that out or augment it. Whenever we are confronted with a minority applicant, it seems to result in an awareness of shortcomings in these critical areas with respect to that minority. As an example, I remember interviewing for a position at an academic institution. On the agenda was an interview with a physician of a specialty that had nothing to do with mine. When he and I finally got into the room together and the door was closed, we both laughed out loud at the fact that neither of us understood the reason why we were on our respective schedules. Upon seeing that we were both black males, it became clearly evident as to why we were assigned this meeting. Both of us asked the question as to why someone assumed that this was a meeting either of us wanted. In short, I think it is fantastic that some leaders understand the shortcomings that exist and how those shortcomings impact the ability to recruit and promote minorities. My pushback to these individuals is that perhaps this needs to be tended to in between interview cycles.”

My conversation with Dr. Porter was illuminating; it is clear that institutions need to work on their culture of inclusivity so that it shows in genuine ways to those they are interviewing and so they can “tax” faculty of color less. In the interim, institutions can help support diverse faculty by specifically acknowledging and supporting their mental health and well-being.

References

- Williamson T, Goodwin CR, Ubel PA. Minority Tax Reform – Avoiding Overtaxing Minorities When we Need Them Most. The New England Journal of Medicine 2021; 384: 1877-1879.