It is well known that following the completion of his cases, Harvey Cushing would dedicate time to drawing the relevant anatomy and important surgical steps of a procedure for future record and recollection.1 In fact, Cushing devoted significant time to cultivating his artistry and became a pupil of Max Brödel, one of the influential medical illustrators of the time.2 During this era, pictorial depiction and artistry were critical components in documenting medicine. As an equal counterpart to text, Cushing’s illustrative depictions of his surgeries would remain in a patient’s chart as a critical component for education and reflection. Further, these images were incorporated into his publications and texts, which became immortalized for future generations to reference.3 While one could argue that our current electronic medical record system has blunted the artistic creativity of medical professionals through eradicating the prior natural tendency to draw rather than solely dictate or type medical notes, technological advances present the opportunity for the reemergence of medical art. Specifically, we are now in an era in which digital art can enable the neurosurgery community to continue the artistic legacy of monumental neurosurgeons such as Cushing.

Within the realm of digital art, the field of neurosurgery has embraced various multimedia outlets such as the use of online illustrations, simulation, and 3D printing. In addition, there has been a marked rise in the creation of surgical videos, both as an educational tool and as a publication platform.4,5 While Yasargil was the first individual to record his neurosurgical cases, improvements in recording software within the operating room have established videos as a common and mainstay form of documenting neurosurgical practice. Unlike illustrations which capture individual moments of time, the use of video has revolutionized the dissemination of knowledge and the teaching of neurosurgical concepts. For instance, journals now dedicate sections to highlighting stand-alone surgical videos including Neurosurgical Focus: Video, Operative Neurosurgery, and World Neurosurgery. Additionally, The Neurosurgical Atlas by Dr. Aaron Cohen-Gadol, The Rhoton Collection, social media websites (mainly Facebook and Twitter), and YouTube channels such as AANSNeurosurgery, alongside institutional video collections, serve as public depositories of neurosurgical videos that are available and accessible to all learners.

As an educational platform, surgical videos enable learning for both the creator and for the audience. While pictures may be worth a thousand words, videos are perhaps worth one million words. The use of surgical videos allows for a new depth of concept learning that can surpass what text and illustrations may be able to offer. In tasking neurosurgical trainees with the creation of surgical videos, learners are required to demonstrate a more thorough understanding of the principles and minutia of a procedure than what can be acquired from reading text. The goal in producing these videos is to move towards a more engaged learner and communicator. Creation of surgical videos promotes the highest level of understanding through providing a platform of neurosurgery trainees to teach a virtual audience, thereby strengthening their own engagement and knowledge of surgical cases. While hands-on experience is the gold standard for learning, the creation of surgical videos allows for a higher level of engagement from the learners compared to passive observation.

Similar to how athletes have the opportunity to review their performance, the recording of procedures provides neurosurgery residents (and attending physicians) the opportunity to reflect on and critically assess their performance, thereby highlighting an additional educational utility for videos within the neurosurgical community. As an audience member, videos are an invaluable resource to accelerate the learning curves of neurosurgical residents and medical students, especially if time and interactions in the operating room may be limited for these individuals. Further, surgical videos provide an accessible means of education for resource deplete countries where extensive training with simulators may not be possible. Therefore, it is of great use and benefit for neurosurgical departments to incorporate videos into their practice.

With the multitude of online software programs available, departments and individuals do not necessarily need access to formalized media teams for the creation and editing of high-quality videos. Combining graphics and videos, adding transitions and texts, and recording audio can be performed through video editing software including Adobe Premiere Pro (San Jose, CA), Final Cut Pro (Cupertino, CA), and iMovie (Cupertino, CA).

While Adobe Premiere Pro serves as the gold standard for video editing from our experience, other applications may be more intuitive for the beginner video editor yet are still able to produce high quality videos. Many institutions have subscriptions for Adobe Premiere Pro; however, iMovie is available for individuals that desire a free software program. Precise editing of audio be can be performed using applications such as Adobe Audition (San Jose, CA), GarageBand (Cupertino, CA), and Audacity (San Francisco, CA), which can be overlayed onto the original video file in any video editing software. In addition, the inclusion of three-dimensional reconstruction can enhance the educational experience through effectively highlight the relevant anatomical structures.6

Supplementary Video 1. Three-dimensional reconstruction that was created using Surgical Theater’s segmentation software (Los Angeles, CA). Patient-specific “fly-throughs” are useful adjuncts in surgical decision making and planning.

Supplementary Video 2. Three-dimensional reconstruction that was created using 3D Slicer (Boston, MA). The white matter tractography is used to visualize the nerve tracts and their relationship to surrounding anatomy/pathology.

Representative examples of our surgical videos can be found published in Operative Neurosurgery,7,8 along with condensed versions archived on our Twitter social media platform (@BernardBendokMD and @MayoClinicNeuro).

Alongside the educational benefit of producing neurosurgical videos, digital art as a whole is an invaluable asset to the modern neurosurgeon.

Within the field, there are numerous advocates for the incorporation of art in medicine as it allows for more humanization in the practice of medicine.9 Therefore, why should the incorporation of digital art into neurosurgery be any different? Along with writing, poetry, and physical art, digital art has the potential to serve as a hobby and creative outlet for neurosurgeons. Through encouraging neurosurgeons as a society to embrace our creativity through the digital art, we can reap the benefits of practicing mindfulness, improving communication, and fostering more self-care.10,11 With the abundance of accessible and free resources, this skillset can be incorporated into the repertoire of any neurosurgeon and can serve as a way to further build community within the field of neurosurgery.

Given the increased prevalence of digital media in medical education and journal publications, it is important for neurosurgeons to have competencies in this skill, both for their academic success and their personal growth as a medical professional. Therefore, offering structured training in digital art may be of benefit for neurosurgery residents and physicians. Further, a call to incorporate formalized training in digital art into resident curriculum would serve to ensure the literacy and competency in these skills for future neurosurgeons. By integrating the various forms of digital art together, we have created range of virtual tools which can augment reality and teach concepts using a new approach that was not possible in the past. Ultimately, our promotion and utilization of digital art and surgical videos has allowed the neurosurgical community to enhance engagement in neurosurgical training, increase accessibility of educational resources, and continue the legacy of Cushing and Yasargil at the intersection of art and medicine.

Figure Legend:

Figure 1. View of video editing using iMovie (Cupertino, CA), a free software program. Using this video editing program, users are able to combine slides, animations, video clips, and audio (orange box) into a single product. Videos can be customized through incorporating additional audio, title captions, backgrounds, and slide transitions (red box). The editor has a choice amongst dozens of unique transition options (upper left panel) and can utilize such transitions in between slides and video segments (yellow star). Fine details of individuals video segments can be adjusted through color correction, cropping, and speed enhancement (green box). In addition, media can be added between video segments through the “Split Clip” function, and important moments of the video can be highlighted by stopping on a particular view through the “Add Freeze Frame” feature (blue arrow).

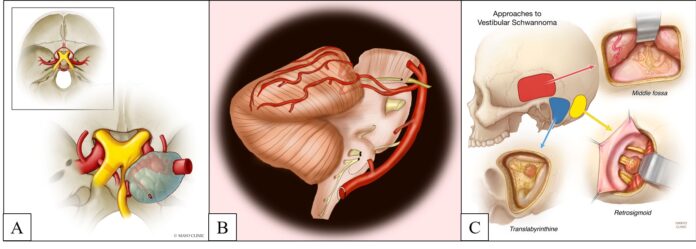

Figure 2. Examples of digital art created within our Department of Neurologic Surgery. (A) The illustration demonstrates the utility of medical illustrations in depicting variations in anatomy or distorted anatomy due to the presence of pathology. The boxed image shows normal internal carotid artery (ICA) anatomy, whereas the unboxed image shows a variant of ICA anatomy in which the posterior communicating artery and the anterior choroidal artery share a common origin at the supraclinoid ICA. The distortion of anatomy is shown by the lesion encasing the ICA and compressing the optic nerve. (B) The illustration shows the three microsurgical approaches for treatment of vestibular schwannoma. By showing approach options relative to one another, students and trainees can gain a deeper understanding of the rationale, risks, and benefits of each approach. (C) The illustration is an example of digital art created by a neurosurgery resident using a free drawing application on an iPad along with an Apple Pencil.

References

- Sathi S, Rossitch E, Jr., Moore MR, Black PM. Harvey Cushing’s postoperative sketches of pediatric brain tumors. Childs Nerv Syst. 1991;7(1):56-58.

- Patel SK, Couldwell WT, Liu JK. Max Brödel: his art, legacy, and contributions to neurosurgery through medical illustration. J Neurosurg. 2011;115(1):182-190.

- Sugar O. The Surgical Art of Harvey Cushing. JAMA. 1993;269(13):1695-1696.

- Knopf JD, Kumar R, Barats M, et al. Neurosurgical Operative Videos: An Analysis of an Increasingly Popular Educational Resource. World Neurosurg. 2020;144:e428-e437.

- Choque-Velasquez J, Kozyrev DA, Colasanti R, et al. The open access video collection project “Hernesniemi’s 1001 and more microsurgical videos of Neurosurgery”: A legacy for educational purposes. Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:188.

- Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30(9):1323-1341.

- Patra DP, Turcotte EL, Bendok BR. Microsurgical Resection of Dorsal Pontine Cavernous Malformation: The Telovelar Approach Augmented by the Tonsillouvular Fissure Exposure: 2-Dimensional Operative Video. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2021;21(4):E373-e374.

- Rahme RJ, Turcotte EL, Patra DP, Welz ME, Batjer HH, Bendok BR. Normalization of Peri-Arteriovenous Malformation Hemodynamics Prior to Direct Microsurgery: 2-Dimensional Operative Video. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2021;21(6):E541-e542.

- Dobkin PL. Art of medicine, art as medicine, and art for medical education. Can Med Educ J. 2020;11(6):e172-e175.

- Zazulak J, Sanaee M, Frolic A, et al. The art of medicine: arts-based training in observation and mindfulness for fostering the empathic response in medical residents. Med Humanit. 2017;43(3):192-198.

- Dalia Y, Milam EC, Rieder EA. Art in Medical Education: A Review. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(6):686-695.