The following is a transcript of an interview conducted on February 23, 2022. Edits for clarity and clarification have been added.

Andrew Carlson

I am a neurosurgeon at the University of New Mexico. I was born and raised here in New Mexico, and so I’ve grown up with the rich intersecting influences of Hispanic, Native American, and other cultures in this state. For this edition of AANS Neurosurgeon, focused on the “culture of neurosurgery”, I thought it would be interesting to focus specifically on how the cultural framework of our patients can affect the care that we provide. I thought that focusing on our Native population would give both specific insight into the issues related to that population, but also hopefully give greater insight into how to best provide compassionate care to patients whose cultural background and perspective may differ from ours.

By way of background, Native Americans make up just under 2% of the US population, but over 10% of the New Mexico population. Within New Mexico, Native populations are a diverse group, represented by 23 tribal communities, 19 pueblos and four tribes. More than 30,000 American Indians live in the Albuquerque metropolitan area and represent over 100 tribes. The Taos Pueblo village was designated as a world heritage site in 1992. The Navajo Nation is the largest reservation in the United States. The University of New Mexico physically sits on the traditional homelands of the Pueblo of Sandia. UNM has developed an official acknowledgment honoring both the land, as well as the contributions made by Native communities and our institutional commitment to those indigenous peoples.

Despite these declarations, we live in the dark shadow of a legacy of genocide and other atrocities inflicted on the indigenous peoples with long-lasting repercussions. There remain significant healthcare disparities in Native populations. There is a shorter life expectancy, higher rates of suicide, higher violent crime rates, and higher rates of death from traumatic brain injury compared to other racial and ethnic groups. These realities make us consider both how historical and ongoing structural issues such as access to care affect their health. In addition, we must consider how we interact with patients and families in the difficult situations that we often encounter as neurosurgeons.

We are extremely fortunate to have a very distinguished panel, kindly organized by Tassy Parker, a member and elder of the Seneca Nation. She belongs to the Beaver Clan. Dr. Parker is the director of the Center for Native American Health (CNAH), Associate Vice President of American Indian Health Research and Education, and tenured professor of Family and Community Medicine here at UNM.

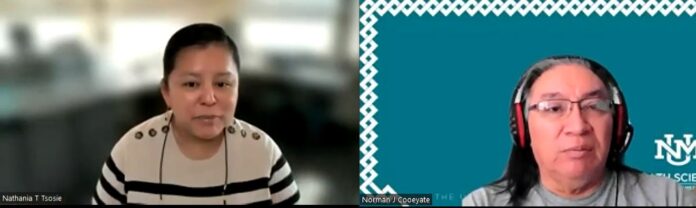

Our panelists include Norman Cooeyate, Tribal Relations Liaison for CNAH and enrolled member and Former Governor of the Pueblo of Zuni. He has been extensively involved in healthcare initiatives within Native communities, as well as research focused on cultural competency regarding research in Native communities.

Also participating is Nathania Tsosie, the associate director for CNAH and a lecturer in the Department of Family and Community Medicine here at UNM. She is a member of the Navajo Nation whose focus has been on community-based participatory research design and strategic implementation. She leads activities within CNAH’s Institute for Indigenous Knowledge and Development, focusing on issues related to cultural humility.

I cannot think of a better group to help us understand these important issues. Thank you so much for making time for us.

Andrew Carlson

Very first I would just like to start with: what is cultural humility and why is it something that neurosurgeons should try to understand?

Nathania Tsosie

I think I can start this off with that question. Thank you very much, Dr. Carlson.

Well, I think cultural humility, at least in the way that CNAH has applied, it is an approach to communication and interacting with people from backgrounds that are different than ours, which means that cultural humility is not just about Native Americans. It can actually be applied to so many different racial, ethnic groups, and different abilities– and just different populations that we work with.

For me, with cultural humility, I tend to prescribe to the definition provided by Tervalon and Garcia, which is that it involves a couple of different concepts. One of the first concepts that is central to cultural humility is this idea of lifelong learning, which is this idea that we’re constantly evolving over time. We’re constantly learning: our entire practice and our entire life course is about learning new things. Because of that, it really complicates the idea of being an expert, as there’s no way to be a complete expert on a concept as fluid as culture. And so, I think it disrupts the idea of mastery, and it disrupts the idea of competency quite a bit. And it puts us in this space where we really do have to be humble practitioners and recognize that we’re not going to know everything all the time. So that, for me, is the first major construct of cultural humility.

The second construct is recognizing the idea that there are power imbalances in the way that we communicate and relate to other people. And those power imbalances can be a result of maybe inherent biases or things that we pick up along the way, (or just kind-of misconceptions), but they can also be because of the different socioeconomic status or even the types of roles that we play. So, a classic example is the relationship between a patient and a provider. There’s a power balance. There’s a power involved with that interaction, and there is a power imbalance as well. So, recognize that there is power imbalance that exists in all of our interactions. Cultural humility is the specific act of trying to address those power imbalances, being cognizant of it, and then trying to do something about it.

Related to that, there’s also this idea that in order to work and create culturally humble relationships, we’re not just being aware of it, but we also do something that actually addresses them on a systemic level. Trying to address health policy or trying to address clinical policy to really change things for a whole population of people. There’s action involved with that as well. For me, that’s what cultural humility means.

I think it really aligns with some of the indigenous core values that we carry as members of tribal Nations. For example, I’m a member of the Navajo Nation. I was born and raised on my own reservation. My first language is Navajo, and one of the core values that we have in my culture is the idea of listening and thinking before you speak. So being very aware of what the space that we’re speaking from, the power that we hold when we speak, and the images that we might put forth through our communication. Cultural humility just aligns with kind of the way that I perceive my day-to-day interactions with people as a Native person. I think, if we really think about it, cultural humility is really nothing new, but it really forces us to think about undoing the way that we’ve been taught in the past. I think a lot of professionals who have been working have this idea of cultural competency as something we talk about quite a bit. And I think cultural humility challenges that idea of competency and sensitivity quite a bit. I think it complicates it. For me, it’s something that I’ve been really excited to explore and to learn in collaboration with Dr. Parker and with Governor Cooeyate. I think I’ll pause there and give Norman a chance to explain. I know he has a very robust understanding of it as well.

Norman Cooeyate

Well, thank you Nathania, and thank you, Dr. Carlson.

Ho’ Norman J. Cooeyate le’ shina, Ho’Dona:kwe deyan, Mula Bitchi:kew a:wan cha’le, Ho’ Shiwi. My name is Norman J. Cooeyate, I belong to the Turkey clan and am a child of the Dogwood Macaw clan, I am Zuni.

The importance of that little utterance is reflected in cultural humility because I said, I am given the name “Norman Cooeyate”, but I referenced that I come from the Pueblo of Zuni in my native language. So it’s already established as a place that I come from that has certain expectations and certain responsibilities. But beyond that, I said that I belong to the Turkey clan and I’m a child of the Dogwood Macaw clan, which already brings forth additional relationships, additional places of where I am engaged and could have conversation, could have responsibilities also, not only as a male, but also as an uncle and grandfather, or even as a person of those two different clanships.

And then in terms of cultural humility, I think Nathania added quite a bit. The challenge that I see from the indigenous perspective is having to bring the Western world into our way of thinking where competition is probably the one thing that I always hear about– through the words of “cultural competency”, “cultural proficiency”, which is nothing that indigenous people even think about. Because at my age of 62, now you would think that I would be competent and I would be proficient in my own culture in my own language, in my own way of life. And I beg to say no, I’m not. I’m probably still in the teens in comparison to other individuals who are way younger than me who have not left the reservation, but have been sort of raised up and been given the opportunity and the responsibility to learn about our Pueblo’s cultures, values, beliefs, and practices. So they are far greater in knowledge than I am. And for me to say that I’m in competition with them is not something that we talk about, or we even utter. As Nathania said, there are cultural values that we hold dear. And one that she mentioned was we take the time to listen to each other before we speak. Having been a former governor, I can tell you that. One of the things that I had to learn to do is to let the people speak before I could even utter my own interpretation of what the situation is and the potential remedy to it. And sometimes, even before I could state that, the discussion from the people have already pointed out so many remedies that all I had to do was basically say, “okay, here’s what I heard, and this is what you said, and this is the action plan we’ll take.” So yes, when it comes to cultural humility and the indigenous perspective, I think it very important that that’s our guiding way of engaging in people.

In my community we have multiple ethnicities, racial minority groups, either married into, or living, or even working. And so cultural humility really is important if we’re going to make our community function as best as we can for the betterment of all of us, not just one individual or couple of individuals. And so with that mindset, I think when I come to UNM and I’m asked to speak on behalf of cultural humility, it’s exactly what Nathania said. The first thing you have to do is you gotta know where you’re from. What are your roots? What are the basic foundations that create who you are? And it’s just not the places that you were born at, that you were raised at, but it’s the influences and the experiences that you’ve had in that journey to point. Nathania and I have different journeys that brought us here to CNAH, but once we got to CNAH, it seems like we’ve complimented each other in terms of our own experiences. She talks about her living back on the reservation and I can relate because I’ve had those same experiences. She talks about her grandparents and I can relate.

When we come here, now we have to look at how Western medicine, academia in particular, looks at culture humility. I understand in the Western world, there is a need for competency because you want somebody who is well-versed in the profession that they chose, to be able to understand everything within that profession so that they could take care of an individual in the most appropriate way. So there’s a competency and proficiency that come into play. Then there’s different healthcare providers that also have to abide by the licensures and the credentialing that comes about. So yes, there is a need for that. But I think beyond that, if we try to engage in cultural competency and cultural proficiency with patient provider relationships, you always have some sort of a blockage to it because in order for you as a provider to take care of whomever is seeking your assistance, you have to also understand what is your own self. What is your background? What are your experiences that have led you up to here and how do they relate to the individual that might be in front of you? And it gives you a better understanding of where do they come from?

Cultural humility also tries, in a way, as Nathania said, to address the power imbalances that are there. I’ve had that experience as a governor where people thought that I should be up front when things happened. I should be the one that received all the accolades when things happened. In a way that’s a power imbalance in my own Pueblo, but I learned earlier from one of the tribal leaders that says, “as a Governor, you’re seen as a warrior, and as warriors, you have the ability to go out and to acquire things for those that aren’t able to stay in the community.” So in a way, when you bring those resources back, you know, you step back and you let the people enjoy the resources. It’s not you that should be elevated because you can’t go get your own resources because that’s what a warrior does. And so in a way, it really put me down to a level where I could relate to the people as they experienced and they enjoyed, or they implemented the resources that came to their hands. Maybe it might be food, maybe might be some sort of resources, you know, like with COVID right now, some people didn’t have enough sanitary products. A lot of people didn’t know where to turn to, if we kept testing and that kind of stuff. So for me, I think I would echo a lot of what Nathania says and fully support this initiative of trying to change the mindset of how people engage. As my dad used to say: “At the end of the day, we’re all the same as human beings, no matter where we come from, no matter how we speak, and how we see. We all bleed the same and our creation stories are no different than that which is preached on Sunday mornings throughout all the churches in the synagogues and other places of worship, because we all speak about a higher power, whoever the name is that we give it to it’s the one in the same.” So that’s my piece. Thank you.

Andrew Carlson

I really appreciate those answers, and I think that leads us well into my next question, which is, do you think it’s possible that culture and beliefs can affect the clinical outcomes of a patient that we’re caring for? For example, I’m thinking when we talk about a patient’s “compliance” with a certain medication after they’ve had a stroke, or if they have a spine problem and we’re giving we’re recommending physical therapy, how could culture affect whether they’re able to continue on with this sort of things that we recommend and how can we affect that as providers?

Nathania Tsosie

I’m a social science scholar, so I tend to look primarily at systems. I don’t think culture inherently conflicts with individual behaviors, but I think it has the ability to influence them. I feel like, especially in Native communities, that social structure is much more telling of people’s ability to adhere to medications than beliefs and values. Like, for example, if somebody does not have access to transportation and can’t travel the distance to get medications or to get the supplies that they need, I feel like that’s a bigger issue that can be addressed by people like us– and should be. I feel like academics and clinical providers have a role to play in advocating for communities to access those same facilitators of healthy behaviors. And to me, structure and infrastructure– the access to all of the basic quality of life facilitators– is really important. And that’s actually one of the key elements of cultural humility: advocating on a structural level. So, its developing partnerships with people and then advocating on their behalf to equalize some of the power and balance. For me, that’s much more telling.

However, having said that, I think that there are some ways that culture can influence our beliefs about medicine or medication or treatments. I speak primarily from my perspective as a Navajo woman and this isn’t to speak for all native tribes. The many tribes are different culturally, linguistically, and the way our social structures are set up. In my culture, I come from a matrilineal culture. So women have a very specific role in our communities, and so I think one of the examples that you might see is that women are more engaged in education and maybe are more engaged in accessing clinical care. We have the research that shows that the people who are more likely to visit the hospital are usually women, for example. So men don’t visit the hospital as often as the women do. So those are maybe some reasons. I personally, haven’t done the research to connect those, but I know that there are a lot of ideas out there about it.

I feel like in my culture, the way I grew up in the 1970s, my grandparents’ contemporaries, were very mistrusting of physicians and hospitals and clinics in general because they felt like once you go to the hospital, you’re only going there to die. And so that was kind of the rhetoric that was going around with my grandparents’ generation. And mind you, my grandparents were from the generation that grew up in the twenties and thirties, right at the beginning of the boarding school era on my reservation. My grandfather had a third-grade education and my grandmother had a fifth-grade education and their first language was Navajo, and they grew up very traditionally. We lived in a very remote part of the reservation, so it was possible to be very culturally homogeneous. It was possible to make a life out there without really having a TV or without having to communicate outside of your little community.

In contrast, my parents’ generation had a very different experience. My parents were born in the fifties, grew up in the seventies, went to boarding school, college, and got jobs. And so they had private health insurance at that point. They became maybe a little bit more trusting of the clinical system, in Western medicine in general, in the same vein. I think they wanted to make it an issue that there’s Western medicine and Native medicine. And there was always this idea that those two are always in conflict. In my case, that wasn’t true. It was always held as equal like they were partners for each other. And I think the clinics on my reservation and in my community really put forth this idea and communicated this image that they were going toward the same goal, that they were partners in health versus adversaries. An example of that is the IHS clinic. The Indian Health Service clinic in Chinle for example has a hogan on their clinic facility grounds. And if a patient wants to see a medicine person, they’ll bring a medicine person into the clinic and have them do our traditional ceremony right there in the clinic. It’s always been a partnership between the two. And I think that maybe it has evolved over time; I feel like I can do both.

I think something that is important to understand about American Indian or indigenous culture is that we don’t necessarily have a religion in the Western sense. We ascribe to spirituality, and spirituality is the way we view the world and the way we think the earth connects with us. So we’re not an organized religion and many of us do belong to organized religions. It’s possible that you could practice both traditional Navajo medicine and be Christian, and you can go to the clinic at the same time. So I feel like some of those ideas that there are only two sides of the coin or that you have to pick one or the other, I think those are going away.

That’s just my personal experience. And my personal kind of reflection on it is I don’t think that it’s as far apart as we think it is, but there is a lot of opportunity for overlap. And that’s why I’m glad to hear that clinics like UNM and others are looking towards something that’s much more inclusive. And I think cultural humility, it gives us a good framework and is a good vehicle for achieving that because it does recognize that those kinds of categories that we thought were there are really not there at all, but there’s much more gray area than we think there is. And the same is true for culture. We treat culture as a scale: there is being truly in-depth, living the Navajo way of life. And I don’t think anybody would ever say that they live truly only that way because of the influence of Western culture on our lives right now. I think we’re a much more global culture and I think that’s the way I feel for my community and what makes sense for where I come from. I’m from a really remote part of the reservation I grew up in Burnt Corn, Arizona. And so, it’s different from say, New Mexico Navajo tribes. And I know the experience is different for Norman though we don’t live too far apart from each other. Being from Zuni Pueblo, his experience is very different because his culture and his community is also set up differently.

Norman Cooeyate

Yes, I think Nathania highlighted the differences between indigenous communities that are spread out quite a bit, versus those communities like a Pueblo, which are very congregated and there are some advantages to that in that there are values that are created, where we protect, we care. We share a lot of things that make one family unit or multiple family units function. The other disadvantage about that is that experiences are easily shared among family members. Nathania did mention that there are some progressive IHS facilities that allow some indigenous practices to be part of the IHS facilities. But in most cases, most IHS facilities are not at the same par as Navajo nation is, so a family member in Zuni, back in the day before we got our modern hospital, would maybe have a bad experience and then they would go home and they would share that within the family. And then, if you’re the one that is supposed to go get care in that facility, you already have a mindset that you’re not going to have a good experience.

And whether that is true or not, it’s just already part of the family lore that people talk about. Even outside of the family setting, when we have social gatherings, people talk about how they were treated by a Western practitioner and how they sort of dismissed cultural practices that they wanted to engage as part of their medical treatment. And so that’s part of what I’ve had to experience in my own Pueblo.

The thing about understanding how cultural and beliefs can impact clinical outcomes is understanding that indigenous people don’t see healthcare as individualistic. They see it as a family unit. As Nathania said, her tribe is more matrilineal and so is mine. It won’t be surprising to actually have women making the decisions on what the potential treatment should be for that individual, including if it’s a male. It also goes as far as what is the standing of that person within their own clan. So it could be a clan decision that is made based on the treatment.

The other part about it too is understanding access to services. You had mentioned that potentially an individual could be getting physical therapy post-surgery and I’ll give you an example that comes from my family. My elder sibling, who is now probably about 85, straight traditional high school education, worked in a gas station for several years and then quit and became a sheepherder. That’s all he’s doing his whole life.

When he succumbed to an infection in his spinal column, there were multiple things that came out. I don’t share this so easily. His perspective was that number one, he did something wrong against the elements of where he was at, meaning he had disrupted his relationship with not only the animals he cared for, but also the land upon which the animals were being raised, including some of the other potential participants within that, like the birds, the bear, the deer, even down to the snakes. He felt that he had somehow disrupted one of those. And that’s what came back on him, and that was his curse.

The other one, although it’s not something that is largely in tribal communities, but still persists in some, is the notion of witchcraft. That’s somebody being jealous of how far my brother has gotten in what he’d been doing, that they took offense of that. And they injected this illness upon him. And now remember, he’s a traditional person. Any modern health provider could dismiss those feelings, but he held onto those so steadfastly and his first treatment of choice was to get a medicine man, which is what we did. And then having to talk to him, we eventually say, okay, maybe I’ll go to the hospital, see if they can give me some pills.

That’s the other thing that I know in my family. It’s always this notion of a pill that treats everything. I have a stomachache, let me go get a pill. I have a headache, let me go get a pill. I have an infection in my leg, let me go get a pill. And it’s because of experiences. That’s what is shared that people think that the cure is the pill. Now knowing that there are other different regimens with him, but his treatment required physical therapy. He really didn’t want to, because number one, his first thought was to go back home because he thought nobody could take care of the livestock as he does in his own way. He wanted to make sure that he would get back quickly to make amends to the disruption that he might have done within those environments that he worked at.

But the other thing that he really missed a lot was just having family around. He lived with the two older sisters and my niece and their kids. So about 15, 16 members in one household; he missed that interaction, and he really wanted to go. It’s a good thing my twin daughters live here in Albuquerque, so we made it a point every night to go visit him right after he had his supper. We would sit, we would talk, we would just basically watch TV and the kids will come and they would play games with him. And so that distance from his usual family was diminished because we were there.

Then the other thing is transportation for him was a big issue. When he got released, although he knew how to drive his own vehicle, he somehow, with that surgery and that physical therapy, felt like he couldn’t drive anymore. He didn’t trust himself. So we had to alternate between family members to get him to his regular appointments, sometimes to Albuquerque. And that’s just some of the things collapsed together with my brother’s experience about culture and beliefs that I hope you take into consideration.

Andrew Carlson

Thank you. Those, are very important observations that I think, answer that question well.

The next question focuses on the family a little bit more specifically. Unfortunately, one of the things we deal with a lot in neurosurgery is patients who have very severe types of conditions like aggressive types of brain cancer, or brain injuries that they’re not likely to survive from. How can culture affect the conversations that we would have with a family about a patient who has terminal brain cancer or may not survive from a severe brain injury or stroke?

Nathania Tsosie

That’s a good question. I think that’s a very difficult conversation to have, and I think we all struggle with it, and there’s no magic bullet. There’s no blanket approach for every community. I think what cultural humility teaches us is the importance of self-evaluation in thinking about ourselves or yourselves as providers, and recognizing what’s happening in the power imbalance, that’s there. Also, just committing to self-improvement, committing to “how could I have done that better?” “How did it go?” Creating some kind of system, and everybody has that system. Everybody has this system, whether it’s just thinking: “Oh, I could have done that better.” I think one way of being culturally humble or getting more culturally humble is to think of every interaction as an opportunity for learning and an opportunity to improve your process over time.

I think when it comes to speaking about topics like that, that are very sensitive, I think it helps to ask a lot of questions up front or at least to get an understanding of who the patient is, what kind of family they come from, wherein the state they come from. And then just getting an idea of where they fall, what are their beliefs about the brain? How do they know how the brain connects to the body? What are their ideas about what that connection looks like? That can tell you a lot. I think about whether a family member or a family is very traditional, meaning traditional in the indigenous way, and ascribes to those values about it. Or if they maybe take a more Western approach, maybe they have Christian or Catholic faiths that their views align with. That can help you temper your communication to speak with somebody like that. I think starting off by asking questions about the patient, getting to really know them well, which I think doctors do really well at already, is a good start.

I think in terms of Navajo culture, I feel like the connection between the brain and the body is very important. The brain is, of course, physiologically the center of our whole system and how things work. And I think that heart for a native people is also very important as well as the stomach. I think each of the organs, each part of our body has a significance. I think when it comes to injuring the head or needing some kind of procedure on the head, it’s always really important to understand how that connects to all of your other senses, to understand the way you experience life. Being very close to our eyes or nose or mouth and our ears, all of those are located in the same region. And so the idea of needing anything happening up here, there’s always this perceived risk that it could affect other parts of the way you interact with the world. I think getting a sense of that world view is really important and kind of talking about those ideas and giving families the opportunity to ask those kinds of questions as helpful.

I think when we talk about those issues, there’s something that I find which is for Navajos. Maybe true for pueblos, Norman can speak to that. But for Navajo, one of the things that is always a really difficult thing to do when you go to a clinic is to talk about death and to talk about the possibility of death. Doctors like to be very clear in their communication. They like to be very forward and they like to tell you what the issues are and they like to get you prepared. I’ve been to a doctor where they’ll say, “well, you know, you should know that this is probably going to happen,” or “this could happen.” And those words carry a lot of power. When you say something like there’s a good possibility, he’s not going to make it, you’re basically saying he’s not going to make it, and we’re not going to try. That is very disheartening to the family, and that can set you up for failure really early on in the communication. It really put you at odds with the family and really hurts a lot of feelings.

I think in those kinds of situations, people really try to have faith. They had tried to be optimistic and they try to put themselves in a space of a Navajo word, which means the beauty way. You try to constantly keep your brain. It’s hard to do that when your family member is in a very potentially dire situation and your teaching tells you think, good thoughts, think happy thoughts, think this. And then you have somebody coming at you who’s the expert who’s then telling you, “you know what, you should probably get ready for this person to not make it.” That’s a very difficult situation.

I think one of the things that I feel like has worked is to take that communication and flip it. Don’t talk about the patient specifically, but if there’s a way that you can say something like, “in the past, this has happened another patient, this is what happened to them.” Disconnect it and make it a story about a third person. I think that helps, instead of saying your daughter, your son, your mom. You’re personalizing it is potentially harmful because you’re then setting the path up for them.

When we first started, I had mentioned the importance of listening and the importance of thinking before you speak in our culture. Your whole head is a very important, very central space, it’s it even goes beyond important. It’s a sacred space. When you say something out loud especially, it becomes the way things are going to happen. You “will” it into reality by speaking it. I think that’s why communication is so central. And that’s why it’s really important to be thoughtful, to sit back and reflect about, how am I going to prepare myself for this conversation?

I don’t think that’s unique to Native Americans. I think any family would appreciate that kind of thoughtfulness from our provider. And that’s why I think, just constantly learning from each of those interactions, having supports available through things like this: seminars and having a safe space to have these kinds of conversations for providers and others. That’s really helpful.

But yeah, I think it’s, it’s a very difficult question to answer because culture is not static. Culture is constantly changing. It’s evolving over time right now, this very second. My culture is changing and it will continue to change. And then, nothing I tell you might be the same. Culture is really also tempered by coloniality. Meaning that our cultures are colonized groups, and so we’re influenced by the colonizer. There’s always room for change. It’s not going to be the same from group to group because of it. And that’s why it’s difficult to think about, but I definitely value forums like this that just introduce the possibility that maybe there’s a different way to do it. Hopefully, we’ll continue to work by altogether. I think I’ll pause there and I will turn it over to Norman.

Norman Cooeyate

Well, thanks, Nathania. There’s not much that I could add, except to reiterate what Nathania said, even in Pueblo culture, it’s difficult to talk about death. It’s even to talk about an individual in that position and saying you’re going to die because in a way you’re already projecting that wish on that individual or the possibility that you’re wishing that to the extended family that might be there. So it’s a no-no that we talk about the individual. We try to do it in a more third-person type of a conversation.

The other thing too is I know culture is totally changing as we speak. So a lot of what I said might have changed also, but it’s also looking at the family, questioning them to see if they understand what is happening, so they thoroughly understand what it means about brain death. That they really understand how the brain is connected to the rest of the body. And sometimes it’s sort of like making things elementary, but as indigenous people, we rely a lot on visual aids. So, if there are processes of having some visual pictures that could help in the presentation, I think that would really help out. The other thing is just to ask the family what would they like for the health providers to provide during this time, and maybe allow some of the traditional practitioners to come in to do some of the ceremonies, that they might see that as a ray of hope. That would be their own personal thing. It’s also understanding that, in this time, we sometimes have to give space to the family and the individual.

I know in the health care system, everything is run on compartmentalized time. If somebody’s dying, you want to push them out so you can get the room ready for another. Sometimes we need to slow that down and let the individual, as well as the family, have their time, (especially when the individual has died) to grieve, to share their moment, the last time with them before that individual’s body is taken away. Maybe even to sing songs, maybe even to say a prayer or whatever it might be, that brings them back to balance, to some sort of level. That’s probably about as much as I can add to what Nathania said.

Andrew Carlson

Thank you.

On a maybe slightly lighter note, you mentioned a lot having to do with the importance and sacred nature of the head. And one thing that I’m curious about is that there are certain beliefs that I think are specific to our Native population. One of the things that we do that is somewhat unique here is when we do surgery on the head, we save the patient’s hair. How should we do that in a respectful way to give them their hair back and what are the underlying beliefs that make that a respectful practice?

Nathania Tsosie

Well, I can give some context. I don’t know if I can answer that directly, but I can at least tell you a little bit more about the issue around our hair. In Navajo culture, one of the beliefs we have is that the hair is an extension of your thinking process. And it’s a part of your brain for Navajo women. The easiest example is the babies. We don’t cut their hair until after they’ve had their first laugh and said their first word. Traditionally, that’s the way we’ve done it. Not all families do that, but the belief was that when a baby is born, you let their hair grow until they actually speak, and then you cut their hair. For women in our culture in Navajo, we usually don’t cut or treat our hair until after our first puberty ceremony. And then, you keep it growing and so forth.

There are other tribes that are much more strict than we are, but those are some of the beliefs around it: the belief that your hair is an extension of your, of your thinking, of your words, of your prayers. It’s really important to maintain it in the natural.

However, that said, that’s why it was so difficult during the boarding school era of the 1950s when one of the ways that the boarding school system enacted violence on our children and our people was to cut their hair off immediately. And there are so many stories out there of Native children just crying and crying because their hair was cut. And there’s a lot of trauma around that still around, you know, having your hair cut. So, it connects back to those early days of having their hair cut and their identities basically removed and forcefully removed. It can be a traumatic reminder for some people.

I think about how to treat it and how to respond to it. I appreciate that UNM hospital is giving people the option and asking questions about that. Some people like to burn their hair after they’ve cut it or removed it. Some of us maybe have adopted more Western views where maybe we’re not as strict with how we treat the hair. So, it’s good to ask. And I think it’s every individual family’s choice about how they want to treat it. A similar issue shows up with limb removal, with diabetes, and they remove pieces of the body. How do you treat that? I don’t know if we’re there yet with that kind of issue, but yeah, I think I just appreciate that you’re asking, and I just appreciate that you know, about it, and that there’s room there for the family to make that decision.

Norman Cooeyate

It’s not only the hair, but it’s any part of our body that is displaced from our individuality that has to be treated in a respectful manner. Hair, I guess, particularly when it comes to shaving the head, if it’s just collected in an appropriate manner and may be placed in a plastic receptacle and given to the family. Just to say, “there are some indigenous people who have beliefs about hair, and so we took it upon ourselves to save the hair from this individual and give it to them and let them choose what they want to do with it.” I think would probably be the best approach without trying to figure out why is that they want to save the hair.

Andrew Carlson

Thank you.

My last question, I know that you both really address this quite eloquently already, but I just wanted to give a final opportunity for advice that you have for neurosurgeons who take care of a very diverse population from different global backgrounds across the country and across the world. What are ways and how should neurosurgeons try to be flexible to respond to the different cultural needs of patients, families, and communities that we care for?

Nathania Tsosie

I think an easy one is to travel. You know, if you want to learn about Navajo people, go visit some Navajo people. If you want to learn about Zuni, go to Zuni. And I think it’s really easy. Well, maybe not so easy for doctors who don’t have a lot of time, but I encourage you to get out there and actually take a look at where we’re living and take a look at the kinds of communities we grew up in. So, you can see what it’s like to live the rural area. If you can’t travel and you can’t get out there and actually see these places for yourself, then there’s media. There’s so much out there that you can educate yourself. We’ve been writing ourselves since the seventies since we learned how to write and read English. So, there are tons of books out there, and there are a lot of Navajos out there too.

I think getting out there, having a curiosity, asking questions and listening is really important. Listening and reflecting, because it’s not just enough to ask a question or to barrage somebody with questions. It’s really about listening to it, sitting back with it, reflecting a couple of days and then making it a part of your heart and your hands; the way that you do things– it’s embodied.

In that way, I think our indigenous culture is a lot like other indigenous cultures around the world, that we have this belief about learning, and it’s about why it’s a lifelong process. I think getting out there, getting exposure, asking questions, coming to see people like myself and Norman at CNAH on your own, that’s a good first step.

I think the other thing too, is getting involved in educating yourself about maybe the social determinants of health, of course, and also some of the policy issues, and looking for places where you might be an advocate for Native patients. I think asking questions of yourself like, “how would this look for Native people?” “How can I advocate not with this mentality?” Not like “how can I save people,” but “how can I support this effort and how can I better understand this effort?”

I think those are some easy ways. I mean, the, the beauty, I would hope that one of the reasons why you practice here in New Mexico is because of the beauty of the place and the cultures that are here, and to not be able to experience that in person is, is such a disservice. If you do that, you’re missing out the whole beauty of the place, if you don’t actually go there in person. Native people are very polite. We really believe that in order to gain knowledge, you have to be there in person and you have to communicate face to face and you have to be standing on our sacred land to understand it. And by sacred land, I don’t mean like funerals, but I mean, like within our four sacred mountains on Navajo. Take a chance to go over to Grants. One of our four sacred mountains is Mount Taylor. And so just to experience the beauty of the place because there’s power and there’s knowledge in those places. And if you open yourself up to that, I think there’s, there’s a lot of room what you can learn from, from even the earth.

Norman Cooeyate

I think the only thing I can add to Nathania is you also need to understand the historical context of the indigenous people that you’re working with. Understand the atrocities that they have to go through and not only endured, but resisted, and became resilient, and they’re still here. So, particularly with the two tribes that we represent, you need to know about the Navajo long walk and what that entailed. What does it mean now? Understand about the Pueblo revolt. Why did that happen? Because it has both elements of our own cultural values, beliefs and practices, not being acceptable to the colonial people who were wanting to basically annihilate us. But it’s never talked about in, Western history or any other type of academic class until you get to college. But then, it’s only a sparse and that adds into how indigenous people are receptive and build trust when it comes to healthcare. And that kind of explains a lot, including what Nathania talked about: the boarding school, how it impacts education, how it impacts employment, healthcare, economic development, land revitalization, sacred space, intrusions, all of these things. I would ask you to learn a lot more about that too.

But I think for me in closing, what I could advise somebody like you, Dr. Carlson is just to say, how would you like your family member to be treated if they were in that situation where you were the provider. Say it was your mother, say it was your wife, say it was your child. How would you like for them to be treated? And if it’s not by you, by one of your colleagues. I think if you understand what I’m saying about that, then you start to understand a little bit about what Nathania has started out with giving you a definition of what cultural humility is.

It really brings it down to where power imbalances are being addressed. Because now you’re looking at it from your own relationship to that person that you’re treating. I hope that you know, what little we shared with you goes a long way. And that’s the thing you said, we’re both learning as we’re speaking to you, but we also have the ability to teach from our own experiences individually and collectively. Now we’ve been at CNAH together for 10 years, so we’ve learned a lot. And I just want to thank you for asking us for a little bit of our time today.

Andrew Carlson

Well, I thank you both so much. That was certainly a very meaningful opportunity for me. And I’m very hopeful that it is going to have a similar introduction to trying to learn more and understand these issues better for others in the field. I really appreciate both of your time and think that was just a fantastic discussion.