For surgeons, wearing a mask feels normal – it’s part of our everyday life. The past few months, however, have demonstrated that this familiarity does not extend beyond the operating room. Donning masks at all times while in hospital is one of many daily reminders of how much the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our world. While the morning temperature checks, socially distanced elevator rides, and empty hallways have shaken our routine, the changes in how we communicate (both with patients and with each other) as well as the mental health stressors that permeate our daily thoughts, underlie the new reality for neurosurgeons in 2020. Despite these new realities, this pandemic has revealed the resiliency and adaptability that thrives in this environment, allowing neurosurgeons (and all humans) to cope. The Cleveland Clinic (CC) Department of Neurosurgery’s experience highlights these concepts.

Taking our Pulse

The senior author (ECB) recently wrote an editor-in-chief letter in World Neurosurgery describing the wide range of emotions and sentiments our residents felt during this pandemic. The most prominent of these were fear and guilt. The fears predominantly were centered about:

- Our own safety and the safety of our family while treating patients with unknown COVID-19 status

- Speaking out about one’s own safety concerns or the concern for insufficient safety measures.

- How the pandemic will affect resident training and job prospects upon graduation?

Guilt came in two forms. The first is associated with feeling guilty regarding the fear of the patient as a potential threat. We should not fear the patient, but we do. The second and common form of guilt was associated with not being able to do enough to help, given the sub-specialized nature of our training. As the author stated,

“We are usually up front leading charges, saving lives, and performing heroic operations…not so these days. This can leave us with a sense of uselessness”.

This extends also to the day-to-day care of our patients. Small gestures that would previously be comforting respites in the otherwise exhausting course of patient care are no longer in accordance with social distancing standards. A comforting touch on the shoulder or hug to a patient with a newly diagnosed malignant brain tumor has been replaced with a concerned eyebrow raised from six-feet away. A familiar smile to the patient affected by a subarachnoid hemorrhage on their 13th day of hospitalization without family members is now hidden behind a surgical mask. The residents and staff in neurosurgery at the Cleveland Clinic experienced all of this in March as the impact of the COVID pandemic struck with the force of a late winter blizzard.

Finding a Treatment

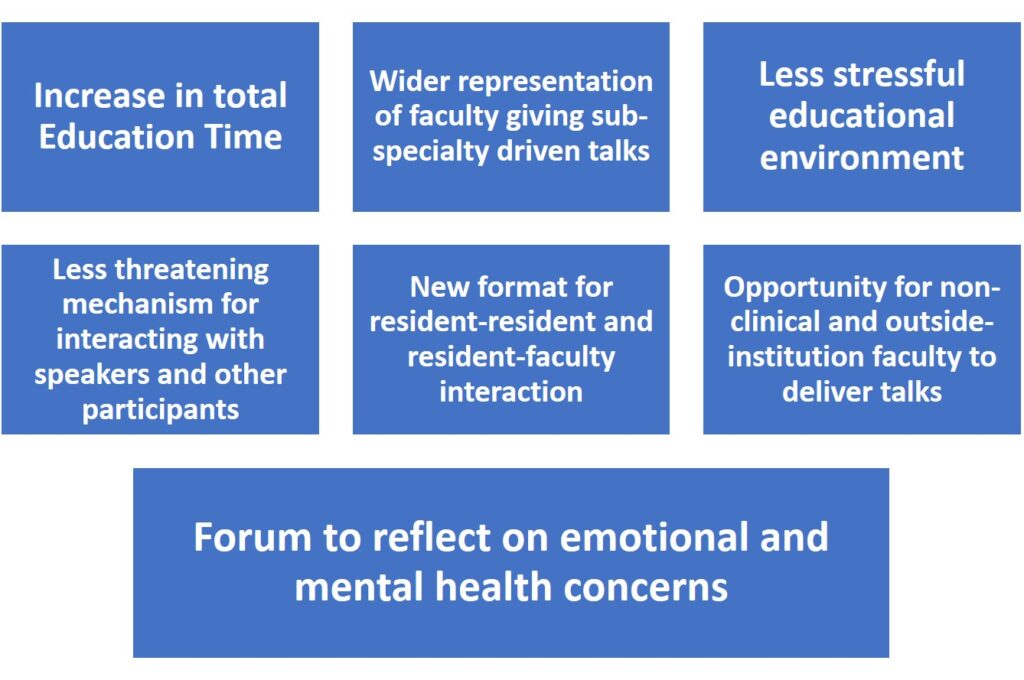

These new realities necessitated innovative ways to connect and communicate both with patients and our fellow team members. By mid-March, all non-essential surgeries were cancelled, the daily in-house complement was reduced to a skeleton crew, and all face to face meetings and conferences were cancelled. Like other departments nationwide, our department made the rapid shift to Virtual meetings and teaching using various commercial platforms. Driven primarily by the residents, but with strong staff support, a two-hour video conference was established each morning (Figure 1). These encompassed all the existing conferences (tumor board, journal club, Morbidity and Mortality, and grand rounds) but also added a comprehensive spectrum of faculty and resident lectures. All residents, a large portion of staff, and even some members of non-Ohio CCF neurosurgery programs participated regularly. Advantages illustrated in Figure 2.

Not only did this provide daily education for the residents, but it also created a new format for resident-resident and resident-faculty interaction and a forum to reflect on emotional and mental health issues.

While virtual meetings have potential limitations, during March and April, these daily videoconferences paradoxically allowed our program to become more connected than ever before; with an emerging stronger sense of team and freedom of expression. Part of almost every day was given over to a check-in with the residents about fears and other psychological issues. Somehow the relative anonymity of the Virtual platform seemed to liberate the residents to express their emotions freely thus allowing for interventions to address individual and group needs. The educational quality of the conferences was monitored by faculty and chief residents.

During difficult times like these, and with the largest burden of mental health challenges falling on healthcare workers1, it was critical to stay connected to provide both a layer of normalcy and an outlet for conversation.

Figure 1. Screenshot of Virtual Teaching Conference

Figure 2. Advantages of daily Virtual Teaching Conferences

Applying Innovation

Downtime is a foreign concept at most busy neurosurgical centers. COVID-19 gave our program the opportunity to focus on research and program development. The Cleveland Clinic (CC) Department of Neurosurgery, including 2 staff and 2 residents, participated in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Program Director Patient Safety and Quality (PDPQ) Pilot. This program has taken on a critically important task: determining the means to insure that resident training includes a solid foundation in key concepts regarding patient safety and quality improvement, while establishing the understanding that these are essential concepts to incorporate into every stage of medical practice. While the concept appears remarkably obvious, historically residents have largely been excluded from these activities. Further, the ACGME understood that finding the optimal mechanism to teach and incorporate these concepts into residency training might require some innovative approaches. The goal of the pilot was to begin to understand that process better. Just three specialties (neurosurgery, internal medicine, and emergency medicine) were chosen to participate in the pilot. Within neurosurgery, 5 programs participated.

The unique combination of new-found time and videoconference savviness resulting from the pandemic facilitated CC involvement in this nationwide program. Initially, the pilot involved only faculty. However, as the March sessions unfolded and with the daily conferences launched, one of those ‘eureka moments’ happened, and the shift was made to invite residents to join the pilot project. Two CC neurosurgery residents stepped up and rapidly became integral members of the group. The benefits were notable:

- CC residents had the opportunity to lead and innovate

- CC residents and faculty interacted extensively and successfully

- All involved gained considerable expertise in the science and key concepts related to patient safety and quality improvement as well as educational aspects of imparting those skills

- New opportunities for career growth and development were initiated.

The department-wide enthusiasm and support has spurred the development of an entirely new curriculum for our residents that is focused on both didactic and experiential elements related to quality and safety. As a result, CC residents are thinking about quality improvement (QI) in a different way. A specific project involves the modification of the traditional Neurosurgical Morbidity and Mortality conference to meet current patient safety and QI concepts has been launched. In a short time, the wheels have started to turn and already are picking up speed.

What’s Next?

While these projects and programs on the surface do not seem particularly grandiose or monumental, they provided a sense of normalcy and connectivity for our team during a period of greatest risk to one’s mental health.2 Much has been learned and achieved, and both the faculty and residents are committed to retaining the best of this as our schedules revert to the prior routines. In the face of a pandemic that appears likely to continue smoldering for the foreseeable future, enhanced communication will continue to mitigate some of the negative effects, both with patients and with our fellow colleagues. At the very least, it is more likely that serious psychological issues will be recognized and identified early so appropriate intervention can occur. While it is difficult to glean a silver lining from an ongoing crisis, which has already claimed nearly one million lives worldwide, the resiliency and adaptability of healthcare workers remains a point of optimism. We must continue to create familiarity out of unfamiliarity; like turning lemons into lemonade.

References

[expand title=”View All”]

1. Pearman A, Hughes ML. Mental health challenges of U.S. healthcare professionals during COVID-19. Front Psych. Accepted July 27.

2. Hall H. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers’ mental health. JAAPA. 2020 Jul;33(7):45-48.

[/expand]

[aans_authors]