The views expressed in this presentation do not represent the official policy or opinion of the United States Navy, Defense Health Agency, Department of Defense or the United States Government.

Neurosurgery graduate medical education (GME) is constantly evolving. The institution of the milestones was a significant step towards competency-based education. As faculty, we are now required by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACMGE) to participate in faculty development to further enhance our skills as educators (Common Program Requirements II.B.2.g). We have a contract with society to graduate safe, independently practicing neurosurgeons. Much as we apply the science of medicine to treat complex disease processes, we must apply the science of education to teach the next generation of neurosurgeons. As such, we should ensure that we base our daily teaching practices and curricular design in educational theory. In this article, we will introduce three concepts in educational theory and explore how they apply to our neurosurgery residents and teaching programs.

Adult Learning Theory

Andragogy is the term used to distinguish the methods and processes used in adult education, as opposed to pedagogy, which are those used in children. Popularized by Malcom Knowles starting in 1950, adult learning theory had four initial characteristics that distinguished it from pedagogy, with a fifth one added later:

1. Adults are self-directed in their learning.

2. Adults draw on their prior experience to learn.

3. An adult’s readiness to learn is based on their social role (i.e. real life experience).

4. Adults learn by solving problems that they face.

5. Internal motivation is key for adult learners.

- So how does this relate to neurosurgical graduate medical education? Our residents, as adult learners, will best learn when they are self motivated and faced with problems they must solve. Whether in their practice as a surgeon, researcher or other role, learning will be enhanced when they are able to draw on past experiences to help shape their solutions. Memorizing facts in isolation is likely to be low yield. Tying those specific facts to clinical scenarios or challenges that they face at work is more likely to result in a better understanding and future application of the knowledge.

Experiential Learning

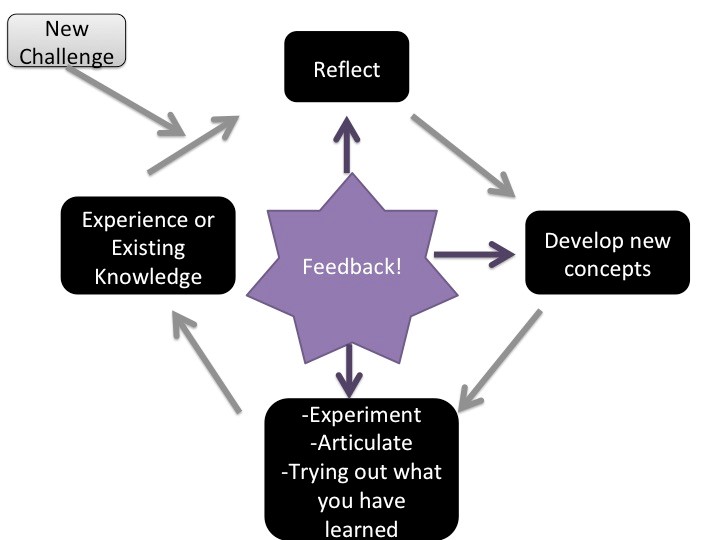

This leads into the theory of Experiential Learning proposed by David Kolb (Figure 1). In this theory, adults utilize prior experience or knowledge to solve a new problem or develop a new skill. Reflecting on the gap between what they know or can do and what they need to know or do creates dissonance, a tension that moves them toward growth. To overcome this dissonance, they further reflect on potential new solutions and develop new concepts to address their gap or challenge. By gathering more information or testing new ideas, they begin to refine the data they have acquired and organize it in a usable fashion. Feedback is critical to this process, particularly as the learner starts to articulate or apply new knowledge. The learner then reflects on the process of how knowledge was obtained, along with the feedback received, and recognize what was learned. Then the cycle starts again with the next challenge or problem presented.

So is Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle applicable to neurosurgery training? Absolutely. Our residents face diagnostic dilemmas daily where they must realize there is a knowledge gap, seek out new knowledge to solve the problem, obtain feedback through supervision, apply it to their situation, see the results, and reflect on what they learned. If we focus on directing the actions of our learners without encouraging reflection, our graduates will not develop all of the skills needed to be independent practitioners and life-long learners. A challenge of Experiential Learning is that learning cannot be optimized without feedback. As with all people, our learners cannot know all that they do not know without external information. Further, early learners may lack the most insight to this problem. This concept is described by the Dunning-Kruger Effect: those with the least amount of knowledge or skill tend to overestimate their abilities. Therefore, the appropriate levels of supervision and feedback are the keys to successful Experiential Learning.

Social Learning Theory

Social Learning Theory can also be used as a model for education in neurosurgery. Lev Vygotsky is credited with developing this theory and the concepts of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) along with the More Knowledgeable Other (MKO). The theory addressing the ZPD is broken down into three main areas: what the learner can do independently, what they can do when guided (ZPD) and what they can’t do, even when guided. The MKO is the guide in this scenario. A resident may have gained a certain skill set that allows them to do a portion of an operative procedure well on their own. Focusing our instruction on this area, which they can already perform independently, would not be optimal. On the other end of the spectrum, pushing the resident to focus on a task that they cannot achieve, despite your direct guidance, would also not be a good use of the instruction. Instead, the learner and the MKO, as a team, should focus on the next set of skills that are attainable with guidance so that enduring learning occurs. Teaching a brand new PGY1 the intricacies of clipping an aneurysm is not likely to be useful. Instead, first focusing on patient positioning and then proceeding once they have mastered this skill reflects using the ZPD. The challenge is that the ZPD for every individual learner is different. This concept is exemplified by the Surgical Autonomy Program that is used to track and evaluate a resident’s operative skills.

Conclusion

While the concepts drawn from educational theory may seem obvious to seasoned educators, understanding the details of these theories can help us improve our curriculum, educational strategies and evaluation systems. Designing educational efforts that are based on educational theory will improve our training programs. This is an exciting opportunity, in neurosurgery GME, to further integrate the science of educational theory with the science of neurosurgery. When properly utilized, educational theory enhances the learner’s experience, improves knowledge and skill retention/application and makes learning more efficient.