Following the theme of this issue, I am going to depart from the standard topics of coding and reimbursement policies for this edition of Coding Clarity, and point out a number of problems with the recently published ProPublica and Consumers’ Checkbook surgeon scorecards. I hope the readers will forgive me for spending some time on a soapbox…

Poor Execution and Confused Methodology of Surgeon Scorecards

Surgeons throughout the country have spent the last few weeks explaining to patients where they rank on the recent surgeon scorecards developed and released on the Internet. The recent publications from ProPublica and Consumers’ Checkbook assessing surgeon-level risk of complication occurrence during elective surgery, combined with their searchable database, look exciting and appear to be a unique use of Medicare administrative data. However, their poor execution and confused methodology has the potential to misinform patients. There are numerous issues with the ProPublica and Consumers’ Checkbook tools. Perhaps worse, the reports detailing the release of these search engines offer identification of individual surgeons with higher than expected complication occurrence. “Naming and shaming” individual surgeons using this poorly-executed analysis is not professional and does not contribute to improving the quality of patient care.

The first issue is one of nomenclature. The ProPublica research effort captures re-admissions after a surgical procedure, reviewing the diagnosis at time of re-admission, and from there decides whether a complication has occurred. The effort uses five years of administrative data obtained from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) for its evaluation. Consumers’ Checkbook uses an algorithm (which they do not share) that assumes a complication occurred when a given patient’s length-of-stay is greater than a risk-adjusted (which they do not define) normative value.

So the ProPublica effort and its surgeon scorecard are not looking at complications at all, but instead at re-admit rates and in-patient deaths. The authors consistently say “complications,” when what they really mean is “re-admissions.” For the re-admissions, they looked at just the principal diagnosis as cause for the re-admission. Approximately half of re-admissions were considered to be secondary to post-operative complications. The researchers do not even try to capture complications that occurred after a procedure during a patient’s initial, index hospitalization. This focus upon complications that are severe enough to merit re-admission does not at all capture what a patient would consider a complication of a given procedure. I am not aware of another example of this approach being used to define complications in the spine-surgery literature. Similarly, Consumers’ Checkbook altogether ignores complications, and only looks at length-of-stay (LOS), 90-day mortality and uses prolonged LOS as a proxy for complication occurrence. Here, again, I know of no similar reports in the literature utilizing this analysis.

Inadequate Risk-adjustment Approach

Many re-admissions may not herald a complication, and many complications may be treated as an outpatient. The highest re-admission rates listed by surgeons in the ProPublica database are actually pretty low, and from the literature are vastly underestimating the risk of perioperative complications in spine surgeries. Also, there are many factors that may drive increased LOS, from patient socioeconomics, to availability of skilled nursing facilities or rehabilitation beds. Assuming a complication has occurred every time a patient’s LOS is prolonged is not valid.

The ProPublica effort analyzes a variety of spine surgeries, where patient and procedure factors may drive complication occurrence. While noting that they review only low-risk, elective spine surgery, they actually are analyzing both low- and high-risk procedures. Over 2,000 patients in the lumbar-fusion (81.07) patient-group are undergoing treatment with a primary diagnosis of scoliosis. For a Medicare-aged population, those procedures are likely reconstructive and not low risk. The researchers do not describe different complication rates in the various diagnosis categories they review.

Risk adjustment is poorly handled by both models. ProPublica uses a “health score,” developed as a modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity score, as its measure of patient medical risk. This score has not been validated in the literature for use predicting complications in spine or other surgical patients. As described, this measure was developed primarily to look at in-hospital deaths, and was developed to allow for a combination of the scoring of the Charlson system with the variety of the Elixhauser comorbidity capture. While this may be valid, and may allow for an estimated risk of in-hospital death, as it is described, scoring methods such as the Charlson are not reliable predictors of complication occurrence and may not adequately gauge an individual’s risk of having a complication. Consumers’ Checkbook reports that they use a risk-adjusted LOS, but then offer no details on how this model was developed.

In the ProPublica effort, the risk-adjustment approach fails. The researchers found little correlation between the “health score” and the complication occurrence, and their interpretation of this finding seems odd. “A notable feature of our model is that the small, but significant effect of the Health Score (per-procedure AUC of .57-.63) essentially disappears when age, and the hospital and surgeon effects are included in the model.” They go on further to note, “This shows that the quality of care is likely a more important factor determining patient outcomes.”

This means their metric capturing the impact of comorbidities functions a little better than flipping a coin when trying to predict whether or not a patient will suffer a complication.

The Effect of Comorbidities

This poor predictive accuracy is evidence of a weakness in the model’s risk stratification, not that patient comorbidities have no impact on complication occurrence. It is logic like this that would keep them from being published in a reputable journal. Just because this model does not show effect of comorbidities, it is specious to claim that comorbidities have no effect on complication occurrence. Not all patients are created equal and, regardless of comorbid condition, not all patients have the same risk of re-admission after an index surgery.

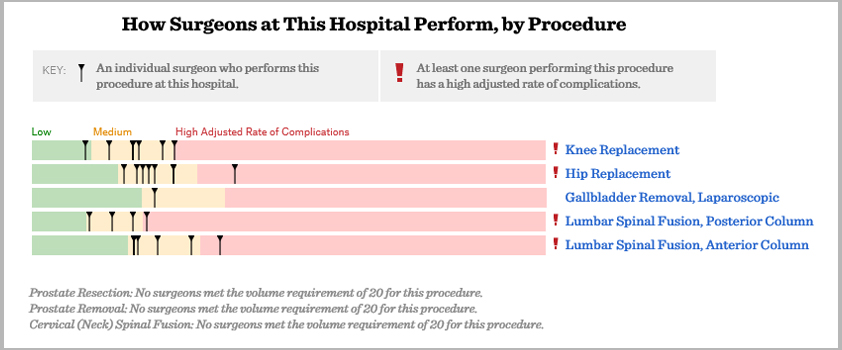

Similarly, the small numbers of re-admissions per surgeon mean that only a few re-admissions may drive a change in score. Looking at the data provided for St. Joseph’s Hospital in Phoenix, for instance, we see that three surgeons have high adjusted rates of re-admissions/deaths. However, the overall number of re-admissions/deaths for all surgeons from St. Joseph’s is less than 10 per surgeon, and hence, not reported. Similarly, no raw re-admission/death rate is reported for these surgeons. Since the total number of re-admissions/deaths for each surgeon is redacted, further analysis is impossible. It is clear that, when low-, medium- and high-risk surgeons are each having fewer than 10 re-admissions/deaths over a five-year data assay, perhaps only a single re-admission could drive a change in risk category.

These Internet-published scorecards feature inadequate risk adjustment, a unique definition of complication occurrence, a muddled patient population and the possibility of sampling error. These critical issues render the ProPublica and Consumers’ Checkbook efforts of limited use. “Naming and shaming” individual surgeons using this poorly executed analysis is not professional, and it does not contribute to the overall goal of improving patient care. Using data to drive health-care decisions is a worthy goal and merits research effort. However, misusing administrative data to slander individual physicians — based upon poorly-executed analysis — is not constructive and aids neither patients nor physicians.

[aans_authors]