Abstract

At most doctor’s offices, responding to patient phone calls represents a significant portion of the typical work day. Requests from patients are many and varied, and the work does not stop when the phone call is completed. Often, there is a dearth of documentation and routing and rerouting of questions and answers before a resolution is achieved. The authors hypothesized that patient phone calls to the office for certain types of medical questions and other information were reduced by video recording the patient-provider visits and allowing patients to watch the visits again at home. This was believed to allow patients to answer some of their own questions without having to call the office. The authors of this study compared phone calls between patients who used the video system and those who did not and found that calls were reduced by 23.9 percent in the video cohort. Separately, staff members were timed doing follow-up tasks relating to phone calls. The average amount of time spent on the call, from the initial pickup of the call to the resolution of the issue, including documentation in the patient’s chart and time spent writing and replying to interoffice messages, was derived using a formula developed by the authors. By calculating cost savings using this information, based on the average salaries of staff members and the authors’ practice’s annual phone call load, the authors determined that nearly $42,000 could be saved at practices by having all visits video recorded.

Introduction

Over the past 40 years, studies regarding the use of telephone to communicate with patients have shown that allowing patients to hear from their doctor outside the normal office visit has a positive impact on the patient. Additionally, previous studies have shown that doctors’ offices spend a large amount of time every day answering questions, providing information over the phone to patients. Most patient phone calls at the authors’ offices come during the post-consultation period before and after having a neurosurgical procedure and are typically questions about what the doctor said or requesting clarifications, appointment information and requests for paperwork (such as Family Medical Leave Act or other disability paperwork). The authors hypothesized that the provision of a personalized video recording of the patient’s visit with the doctor would help to reduce the number of post-visit phone calls made to the office by helping the patient answer some of their own questions by watching the recording, and the number of reduced phone calls could be quantified as a monetary savings to the practice.

Materials and Methods

Beginning in 2009, the authors of this study allowed video recording in their clinical consultations using a video recording and upload system known as The Medical Memory. This system allows the clinical visit to be recorded on a handheld video camera placed unobtrusively in the clinic room and then uploaded to a secure and encrypted website. Patients created a username and a password to access their specific video and were allowed to watch the video as many times as they would like for a period of 90 days following their visit. The Medical Memory video recording system stores videos in the cloud on a secure server with built-in encryption. A typical video for a 30 to 40 minute consultation with a neurosurgeon can be approximately 2.1 gigabytes worth of data to store.

In June 2013, the authors identified a retrospective series of 400 patients — the most recent 200 of whom had used The Medical Memory service and had seen the doctor for their first consultation but had not used the video recording service. Using the practice’s electronic medical record system, the number of phone notes (memos made in the patient’s chart each time a phone call is received from the patient) were recorded for each patient for the 30 days following their visit with the doctor. The text of each phone note was also analyzed and recorded into a reason for why the phone call was placed in one of six categories: medication requests, imaging or testing questions (or requests for results), requests for paperwork (such as disability paperwork), medical questions about diagnoses or procedures, appointment scheduling questions and other requests.

Subsequent to the retrospective study, the authors conducted a time study in their office to identify the average number of calls per week, the average length of a call and the average time it took for a staff member and a provider to fully answer the patient’s inquiry. This was done by asking staff members to record the length of each call they answered over a three-week period in the office as well as the reason for each phone call. The lead author also timed the providers and staff members while performing certain tasks over a different three-week period which included answering phone calls (from call-pickup to call-hangup), documenting calls in the patient’s electronic medical record (EMR), routing messages within and outside the EMR to providers or other staff as appropriate, calling patients back with results from the providers, reviewing imaging results, discussing cases with colleagues or staff members, scheduling appointments and other tasks, in order to produce a series of averages for provider and staff-response times.

Results

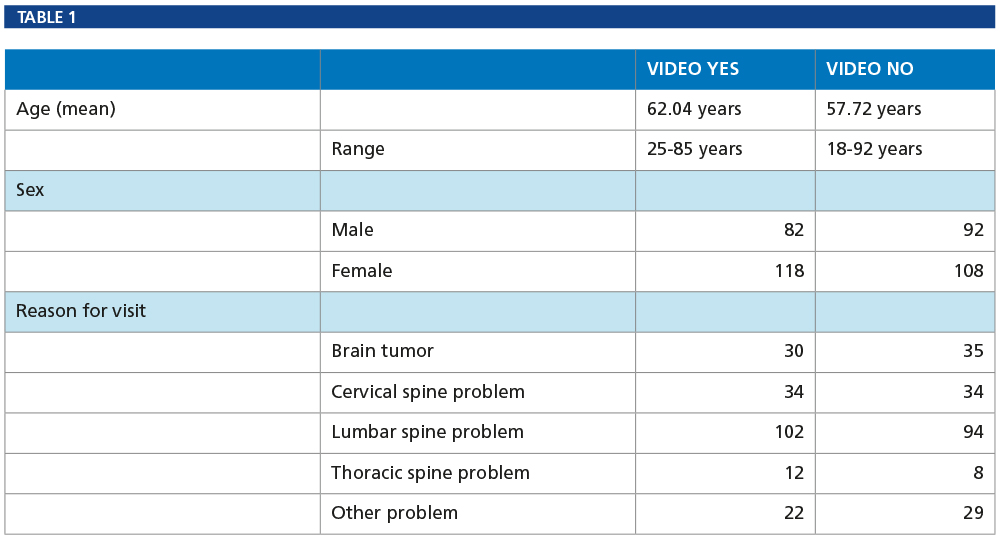

Table 1 presents the demographics of our video-user and non-video-user patients: age, sex and reason for visit.

Phone Notes Study

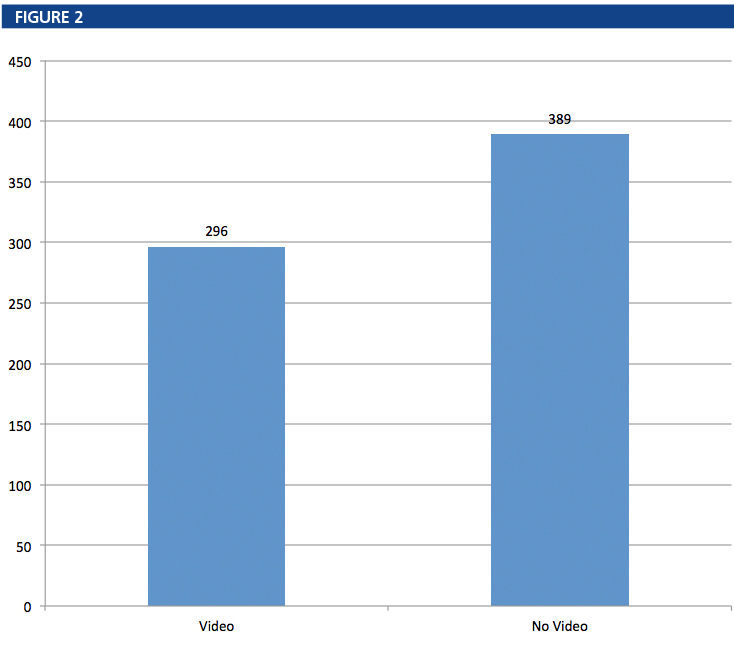

The total number of incoming phone calls in the video-user group was 154, and the total number of calls placed to patients recorded in the chart was 142, creating a total of 296 phone notes. In the non-video user group, 184 calls were received and 205 were placed, resulting in 389 phone notes. Calls placed to patients were initiated to either relay the results of testing and physician reviews, to confirm or schedule appointments or to return a patient’s call.

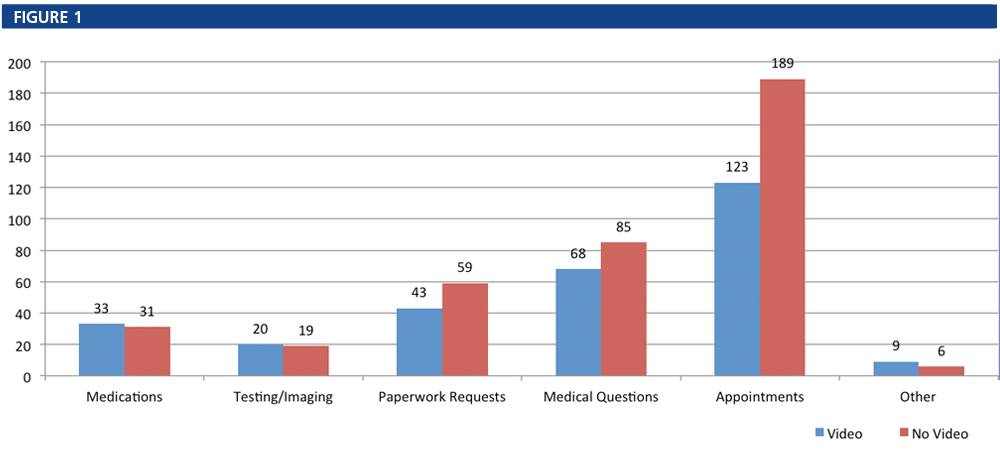

Figure 1 shows the breakdown of calls by reason for the call, and Figure 2 shows the difference in total phone notes by group.

In our study, patients who utilized the video recording service also had fewer phone notes, most notably for medical questions and appointment questions. Questions about medications, testing/imaging and “other” requests were nearly identical between the two groups. Patients who received and watched the video had 27.1 percent fewer requests for paperwork, 20 percent fewer calls about medical issues and 34.9 percent fewer calls about their appointments. In total, the video group had 93 fewer phone calls within the 30-day span following their consultation with the physician, a reduction of 23.9 percent over the non-video group.

In our study, patients who utilized the video recording service also had fewer phone notes, most notably for medical questions and appointment questions. Questions about medications, testing/imaging and “other” requests were nearly identical between the two groups. Patients who received and watched the video had 27.1 percent fewer requests for paperwork, 20 percent fewer calls about medical issues and 34.9 percent fewer calls about their appointments. In total, the video group had 93 fewer phone calls within the 30-day span following their consultation with the physician, a reduction of 23.9 percent over the non-video group.

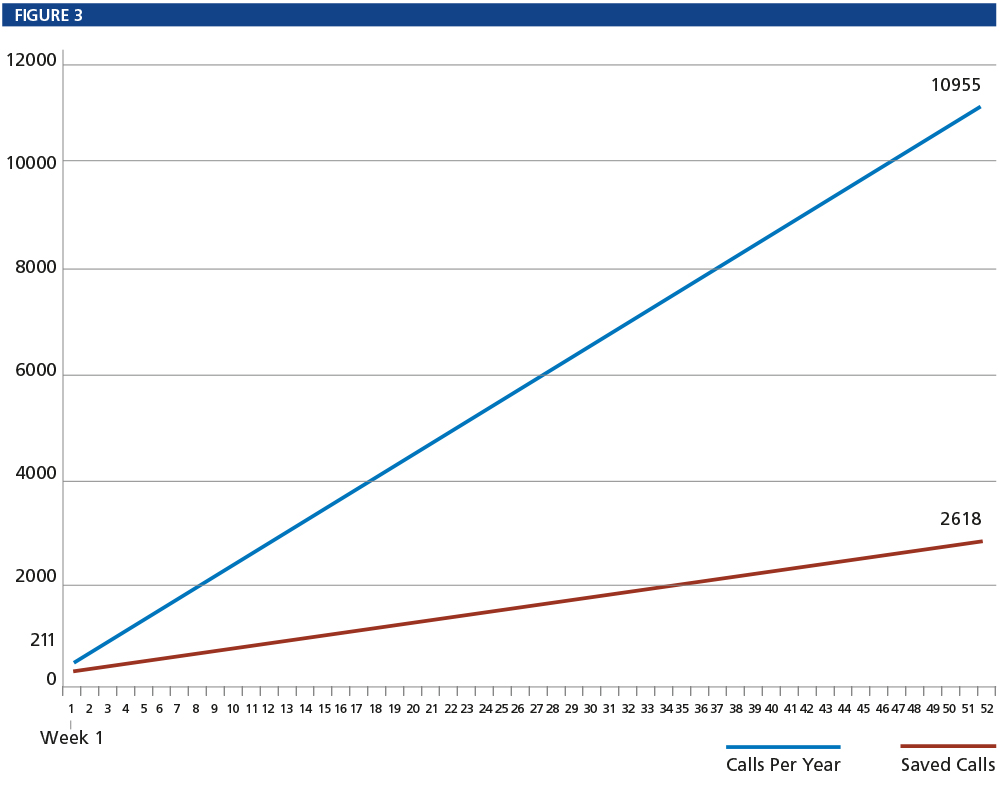

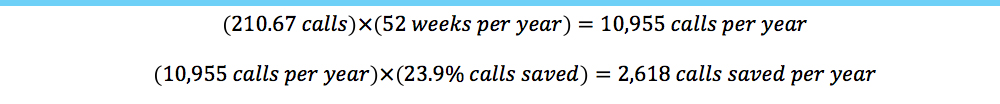

Time Study

In a separate observational period, the authors timed a consecutive series of patient phone calls to their office and discovered that the average length of a call was two minutes and 20 seconds. In addition, the authors categorized each call by topic. Calls for medical questions and general complaints were those hypothesized to be most responsive to use the video-recording service and were longer, averaging three minutes each. The average number of answered calls to the office was 210.67 (plus voice mails per week), multiplying that by 52 weeks per year gives the office’s annual call volume (estimated) as 10,955 phone calls per year. Using the video system reduced weekly calls by 23.9 percent, so the number of calls saved over a 52-week period on average is 2,618.

At the authors’ offices, we timed the actions of our providers and medical staff during business operations to provide a baseline average time to respond to a patient phone call. The average time a provider spent reviewing the patient’s chart and establishing a plan was approximately four minutes and 45 seconds. The average charting time for medical staff to document the initial phone call and the return phone call was approximately two minutes and 30 seconds. The average return call time was approximately three minutes and 45 seconds. This produces a provider time of four minutes and 45 seconds and a medical staff total time of eight minutes and 35 seconds per patient to handle one phone call. Of the provider time, approximately 80 percent of the documentation and patient response time was accomplished by the nurse practitioner; approximately 20 percent was handled by the neurosurgeon.

Cost Savings

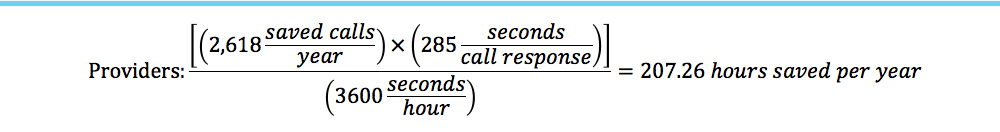

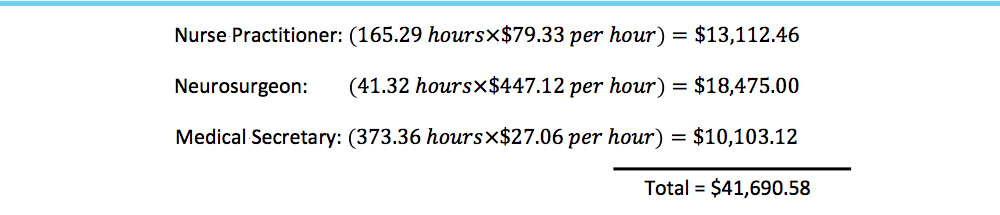

As established above, our office has 210.67 phone calls — plus voice mails — per week, on average. Multiplied by 52 weeks per year, our office gets 10,955 calls per year. This number multiplied by the percentage of saved calls per week (23.9 percent) from our study results in a mean of 2,618 patient phone calls saved per year by using the video system.

The time a provider spends responding to an average phone call is 4 minutes and 45 seconds. The time a provider’s staff spends on taking, documenting and responding to an average phone call is eight minutes and 35 seconds. Multiplying the number of calls saved per year (2,618) by the response times per call for providers and staff produces a total of 207.26 hours saved for providers and 374.52 hours saved for medical staff per year.

We also factored in the 80/20-percent split for the nurse practitioner (NP) and neurosurgeon to produce a more accurate calculation. NPs, therefore, were saved approximately 165.29 hours per year, and the neurosurgeon was saved approximately 41.32 hours per year.

The average salary including benefits for a medical secretary at our practice is $56,284 (or $27.06 per hour). The average salary including benefits for a nurse practitioner at our practice is $165,000 (or $79.33 per hour), and the average salary (including benefits) for a neurosurgeon at our practice is $930,000 (or $447.12 per hour). Therefore, multiplying the hours saved per year by the average annual hourly salaries for each group produces a savings of $13,112.46 for nurse practitioners, $18,475.00 for neurosurgeons, and $10,103.12 for medical staff, or a total of $41,690.58 annually.

Discussion

Use of a personalized video-recording system may enable patients to answer their own questions about what the doctor had told them during a visit. This, in turn, saves the patient a phone call to the doctor’s office to ask that question and frees up both the provider’s time and his staff’s time from answering, documenting and returning the call. In our busy neurosurgical office, this cost savings translates to several hundred work hours and thousands of dollars in estimated annual savings.

Curtis (1) documented that between 15 and 20 percent of all primary medical contacts in the U.S. occurred by telephone and that 60 percent of calls were for medical advice or treatment questions in a primary-care practice. Johnson (2) found that more than one-quarter of all daily patient contacts with general internists in 1990 occurred by telephone — a number that surely has increased with the proliferation of handheld mobile communications devices.

Other studies (3-5) have shown that the number of calls to physicians can average from 100 to 142 per week, just for medical advice (or treatment calls) that are directed to the physician to answer directly. This number excludes other administrative calls from patients, such as calls for directions to the office, the office fax number, appointment rescheduling or any number of other non-medical reasons. Farber (6) found that time spent outside of normal clinical office hours responding to messages and returning calls could be as high as eight additional hours of work per week for the average physician.

Few studies have attempted to address means of reducing superfluous calls to the doctor’s office. Cohen (7) implemented an intervention to reduce medication request calls to a family practice by disallowing any phone requests to be filled and instead had patients bring their medications to an office visit to be discussed and tailored to the patient, which did reduce phone calls but instead, increased office visits. Email communications were studied as another method to help increase doctor patient communication, but Leong (8) found that both the volume of messages received and the time it took to answer those messages was approximately the same for physicians using email versus the telephone.

Audio- and video-recorded consultations have also been studied for their effect on patient recall (10-17). In the majority of studies involving an audio or video intervention, recall was improved in the study populations; however, no study found has included the effect of providing a recording to patients on the potential reduction of follow-up phone calls to the office.

By analyzing phone notes made in our EMRs, we found that the number of calls made by patients who had viewed the appointment video from their visit was significantly less than calls made by patients who had not been recorded. The cost of a single patient phone call is widely variable depending on the complexity of the patient’s request and the amount of time and number of people involved in answering the call. Medical secretaries are not the only people affected by an incoming patient phone call. Providers must spend time analyzing the patient’s requests and replying to the patient or staff members, reviewing imaging, documentation and collaborating with other physicians. Medical staff must answer the initial phone call then spend additional time documenting the call, discussing with the provider, documenting all follow-up in the patient’s EMR and must call the patient back with a plan, if one was not established during the initial phone conversation.

When we combined the number of phone calls with the time it took for staff members and providers to process and respond to a call, we were able to produce average times for things like documentation and creation of phone notes, discussions among staff and providers and imaging reviews. To our knowledge, this represents the best known data for the amount of time a given staff member or provider spends responding to a patient’s phone call. It is unsurprising that by reducing the number of phone calls to the office, doctors can save time and money – up to many thousands of dollars which might be better spent elsewhere in the practice or on patient care.

Conclusions

Providing our patients with access to a personalized video recording of their appointment with a physician reduced phone calls to our office by 23.9 percent. This reduction has the potential to greatly impact a practice’s efficiency. A single patient phone call takes over 13 minutes to complete from the moment the phone is answered to the successful resolution and documentation of the patient’s questions. This means that each phone call costs practices a quantifiable monetary amount, which, when annualized, aggregates to several thousands of dollars. The authors believe that more widespread use of personalized video recording in medical encounters could have a significant impact on the fiscal stability of many practices and providers.

Limitations

Our study is limited by the fact that we did not examine whether or not the phone call in either group is something that was discussed by the physician during a patient’s appointment. If the doctor did not discuss something with the patient, it might not have resulted in a saved phone call to the office. Conversely, if the doctor did mention something on a video, but the patient called anyway, this would impact our final results. A potential confounding factor in this study is the actual documentation of phone notes themselves. Many calls may not have been recorded in the chart if they were simple requests for information, such as for when a patient’s next appointment is scheduled. In addition, the projected cost savings may not be appropriate to generalize to all other specialties. Offices that see fewer patients can be expected to have fewer phone calls to the office annually. Future research is warranted to determine more precisely the impact of providing consultation recordings to patients regarding the reduction in patient follow-up contact to the physician’s office, including average length of calls for specific issues and the potential financial benefits of reducing phone calls in the office.

Conflict of Interest Statements

Andrew J. Meeusen, MA, Barrow Neurosurgical Associates: Shareholder, The Medical Memory LLC; Randall W. Porter, MD, Division of Neurological Surgery, Barrow Neurological Institute: Board Member, The Medical Memory LLC; Shareholder, The Medical Memory LLC.

[aans_authors]

References

1. P. Curtis, A. Talbot, The telephone in primary care, J Community Health. 1981;194-203.