The greatest athletes and musicians practice diligently to master their craft, as evidence suggests natural talent is not a major driver of expert success. In his book “Outliers,” Malcolm Gladwell argues circumstance, practice and chance drive people labeled ‘naturally talented.’

The greatest athletes and musicians practice diligently to master their craft, as evidence suggests natural talent is not a major driver of expert success. In his book “Outliers,” Malcolm Gladwell argues circumstance, practice and chance drive people labeled ‘naturally talented.’

We learn many skills in neurosurgery by passive practice, characterized as experience. Case minimums ensure repetition of the core cases in neurosurgery delivering passive practice. However an intentional, broken down and goal-driven type of practice (or deliberate practice) has been shown to improve skills and surgical technique.

Challenges to Implementing Simulation

So, why isn’t it a standard part of neurosurgical training worldwide? What keeps residency programs and organized neurosurgery from integrating simulation and deliberate practice into training and standards for graduation?

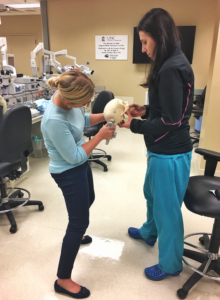

Historically, we have thought of simulation and practice in neurosurgery as cadaver-based dissection, but cost, availability of tissue and lab space are major barriers to this type of practice. Moreover, it is difficult to have repetition with cadaveric tissue due to expense and availability. The next generation of simulation practice has been the generation of task-specific simulators. Cost is a concern, as some of these commercial made simulators are expensive, while some ‘homemade’ models can be very low cost. Barriers to implementing this into surgical education are space, expense and limitation to the one task for which the simulator is designed. Simulation development represents a booming area of educational research, with 283 published simulation-based articles in 2019 alone.

Historically, we have thought of simulation and practice in neurosurgery as cadaver-based dissection, but cost, availability of tissue and lab space are major barriers to this type of practice. Moreover, it is difficult to have repetition with cadaveric tissue due to expense and availability. The next generation of simulation practice has been the generation of task-specific simulators. Cost is a concern, as some of these commercial made simulators are expensive, while some ‘homemade’ models can be very low cost. Barriers to implementing this into surgical education are space, expense and limitation to the one task for which the simulator is designed. Simulation development represents a booming area of educational research, with 283 published simulation-based articles in 2019 alone.

Breaking Down Barriers to Simulation

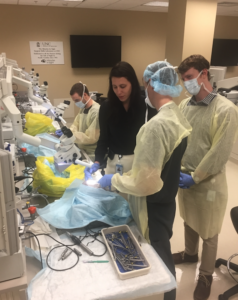

I would argue the most fruitful area to integrate deliberate practice in neurosurgical training is in microsurgical technique. The simplest method to implement microsurgical technique practice is to enable residents to critically review their work under the microscope or by recording. Low cost micro instruments are readily available, and loupes or microscope apps on a phone are sufficient for suturing gauze strands together, suturing artificial vessels, or dissecting placenta vessels. While this was a weekly skills lab in our institution, COVID-19 has forced this to become virtual lab; an instrument set and phone holder cost less than $200/resident. While this initially felt like a hindrance to education, the residents felt empowered to practice deliberately on their own time, with weekly virtual sessions for advice and feedback. They can critically review their dissections recorded on their phone to improve on targeted skills. Even when lab sessions resume, this at home self-driven practice will continue.

I would argue the most fruitful area to integrate deliberate practice in neurosurgical training is in microsurgical technique. The simplest method to implement microsurgical technique practice is to enable residents to critically review their work under the microscope or by recording. Low cost micro instruments are readily available, and loupes or microscope apps on a phone are sufficient for suturing gauze strands together, suturing artificial vessels, or dissecting placenta vessels. While this was a weekly skills lab in our institution, COVID-19 has forced this to become virtual lab; an instrument set and phone holder cost less than $200/resident. While this initially felt like a hindrance to education, the residents felt empowered to practice deliberately on their own time, with weekly virtual sessions for advice and feedback. They can critically review their dissections recorded on their phone to improve on targeted skills. Even when lab sessions resume, this at home self-driven practice will continue.

Beyond Hands-on Simulation

Other areas of valuable surgical simulation are mental rehearsal, time management and communication. Walking through aneurysm rupture, junior resident task management prioritization with simultaneous competing tasks, and navigating communication with hostile staff and patients are all successful simulations practiced in our program.

Simulation practice fosters the habit and culture of deliberate practice in our trainees, as neurosurgical skill mastery should be a lifelong practice.