Movements are calculated and precise. There is forward momentum, directed with singular focus at completion of the task at hand. The rest of the world is a haze, irrelevant. There is a quiet, internally and externally, a balance centered as if on the end of a deep breath caught just before exhalation.

When the pen is finally laid down and the drawing complete, it is as though that breath has finally been exhaled. Time resumes and the world floods with activity and color anew.

The worlds of art and surgery – especially those of illustration and neurosurgery – may be more interrelated than they appear at first glance. I have drawn since childhood and completed majors in Neuroscience and Visual Arts prior to starting medical school and discovering Neurosurgery. Even during my brief tenure in the field, drawing has served major functions for me, and I believe its utility is generalizable to a broader population. Drawing can serve a role in surgical skill building, learning anatomy, educating patients and combating burnout. These skills sets can be acquired rather than simply inherently ingrained.

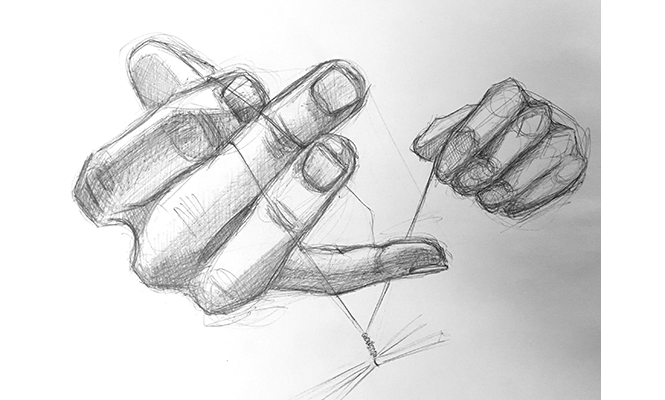

Perhaps the most obviously overlapping skills are those of fine motor control and proprioceptive awareness. These are skills that are learned and honed studiously in the visual arts fields- training reflected in the progressive development of white matter tracts specific to perceptuomotor integration.1 A favorite training tool in the art world is the “blind contour drawing” during which the artist can only look at the object that they are drawing, not at the drawing implement or paper. During my training, I was also taught to draw in a mirror and to draw upside down as ways of strengthening those same connections. Studies have demonstrated the utility of using simulators and animal models in surgical training in order to teach hand-eye coordination as well as gaze and motor feedback, but these training paradigms are limited by availability and accessibility of training materials.2-4 Learning to draw may present a feasible alternative for surgery residents, particularly in the Covid era of social distancing.

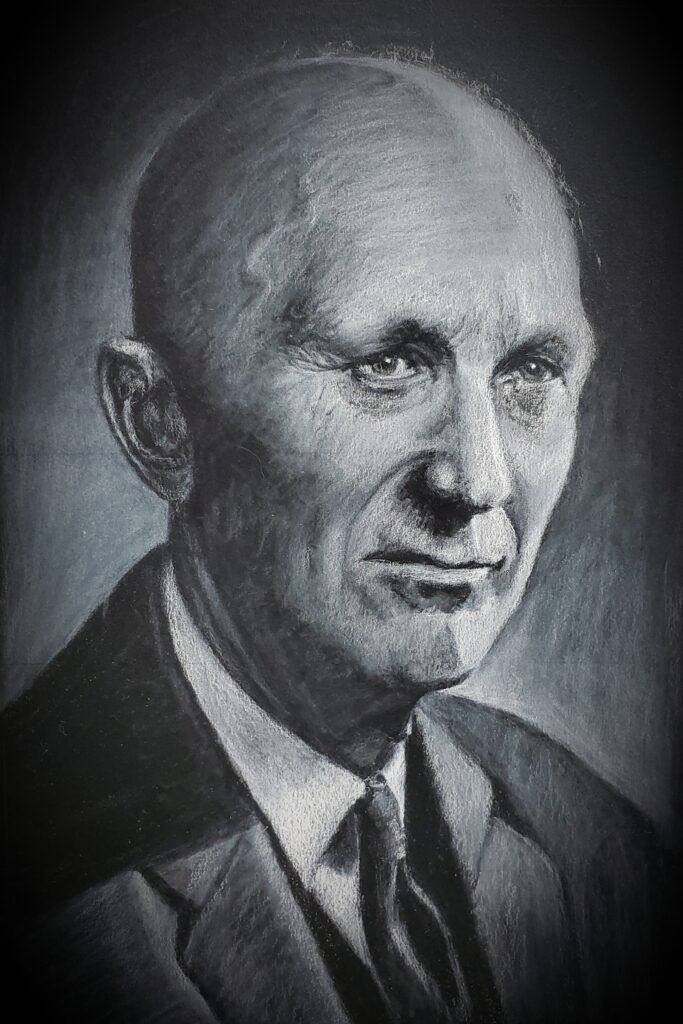

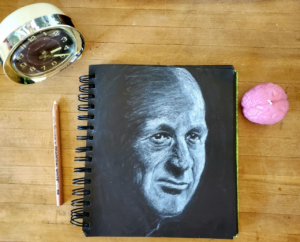

One survey including all types of surgeons demonstrated that 71 out of 100 respondents expressed interest in learning to draw,5 a penchant supported by the existence of courses like “drawing for surgeons” and “sculpture for surgeons.” The “artist-surgeon” phenotype is not novel in neurosurgery; practioners of both disciplines include Keith Kattner, Kathryn Ko and Harvey Cushing. Those planning to enter the field have displayed a predilection for drawing as well, as described in the article “The Art of Neurosurgery” by medical student and artist Remi Kessler.6

Art has repeatedly been shown to significantly aid in learning and memory processes. The popularity of series like “SketchyMedical” and “PicMonic”- which utilize narrative and illustration to aid medical students in learning microbiology, pharmacology and physiology- speaks to the power of the visual memory aid. Drawing specifically has been shown to benefit learning in kindergarteners,7 those with dementia,8 and medical students alike.9-10 In one survey, 83% of surgeons already utilize drawing as a way to study or make notes.5 Drawing is also a promising aid in the planning and recall of procedures. Mental rehearsal- a carryover from the sports physiology field- has been shown to improve surgical performance in general surgery residents.11 Perhaps this is why almost half of surgeons in one survey sketch their procedures prior to surgery.5 Plastic surgeons often sketch the surgical plan on patients themselves as a method of procedural planning.12

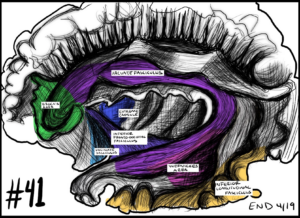

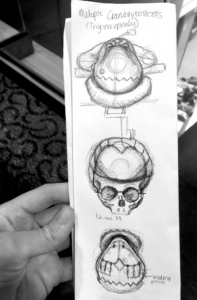

Drawing is also an efficient way to educate both patients and surgical learners. 92% of surgeons in one survey report that drawing is an effective way to communicate with patients. I have drawn subdural hematomas, tumors, strokes and herniation for patients and their families. With every drawing, I feel that I have been able to offer something meaningful. Beyond communication with patients, 80% of surgeons reported it as an effective way to communicate with peers.7 An entire journal, The Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, is dedicated to the advancement of various forms of visual arts in the medical field. Visual communication of intraoperative information is often attempted unsuccessfully via photography which is limited in its ability to separate salient details from noise. It is for this very reason that I have started to illustrate the “Rhoton Top 100” photographs (see “Rhoton #41 below). Edward Tufte, author of On the Visual Display of Quantitative Information, states that “the commonality between science and art is in trying to see profoundly – to develop strategies of seeing and showing.”13 Illustration can focus attention on important aspects of a procedure or process- seeing and showing more effectively than words or photography can.

Finally, drawing is an effective way to relieve stress and practice mindfulness. Small studies in various medical specialties, including Neurology, Oncology and Palliative Care, have demonstrated promising results in combating burnout.14-15 For me, intern year has provided inspiration for a wealth of silly doodles. I have caricatured most of the general surgery resident s’ pets. A curious goat observes the SICU call bed. An “EVD Elephant” trumpets in the Neurosurgery call room, neighboring a scalpel happy turkey and a wise old owl. One of my co-residents and I are respectively writing and illustrating a children’s book on helmet use, starring Robbie Rabbit, a delinquent unicycle rider. Sometimes I draw to learn, sometimes I draw to process a patient’s passing, and sometimes I draw just because it is fun.

Research demonstrates that drawing can serve a role in surgical skill building, learning and teaching of anatomy, patient education, and combating burnout. Given the availability of pen, paper, and a few minutes, drawing may be an efficient, available and healthful addition to neurosurgical training.

1. Chamberlain, R., McManus, I. C., Brunswick, N., Rankin, Q., Riley, H., & Kanai, R. (2014). Drawing on the right side of the brain: A voxel-based morphometry analysis of observational drawing. NeuroImage, 96, 167-173.

2. Sturm, L. P., Windsor, J. A., Cosman, P. H., Cregan, P., Hewett, P. J., & Maddern, G. J. (2008). A systematic review of skills transfer after surgical simulation training. Annals of surgery, 248(2), 166-179.

3. Wilson, M., Coleman, M., & McGrath, J. (2010). Developing basic hand-eye coordination skills for laparoscopic surgery using gaze training. BJU Int, 105(10), 1356-1358.

4. Haluck, R. S., & Krummel, T. M. (2000). Computers and virtual reality for surgical education in the 21st century. Archives of surgery, 135(7), 786-792.

5. Kearns, C. (2019). Is drawing a valuable skill in surgical practice? 100 surgeons weigh in. Journal of visual communication in medicine, 42(1), 4-14.

6. Kessler, R. (2018, June 13). The Art of Neurosurgery. Retrieved from https://aansneurosurgeon.org/aansstudent/the-art-of-neurosurgery/

7. Wright, G. (2017). Drawing in Kindergarten: The Link to Learning in Reading. In Handbook of Research on the Facilitation of Civic Engagement through Community Art (pp. 21-35). IGI Global.

8. University of Waterloo. (2018, December 6). Drawing is better than writing for memory retention. ScienceDaily. Retrieved from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/12/181206114724.htm

9. Borrelli, M., Leung, B., Morgan, M., Saxena, S., & Hunter, A. (2018). Should drawing be incorporated into the teaching of anatomy?. Journal of Contemporary Medical Education, 6(2).

10. James, C., O’Connor, S., & Nagraj, S. (2017). Life Drawing for Medical Students: Artistic, Anatomical and Wellbeing Benefits. MedEdPublish, 6.

11. Arora, S., Aggarwal, R., Sirimanna, P., Moran, A., Grantcharov, T., Kneebone, R., … & Darzi, A. (2011). Mental practice enhances surgical technical skills: a randomized controlled study. Annals of surgery, 253(2), 265-270.

12. Sobel, A. (2019, March 13). Why We Draw on You Before Plastic Surgery. Retrieved from https://www.andersonsobelcosmetic.com/blog/why-cosmetic-surgeons-draw-on-patients/

13. Zachry, M., & Thralls, C. (2004). An interview with Edward R. Tufte. Technical Communication Quarterly, 13(4), 447-462.

14. King, J., Walls, B., Zauber, S., Hildebrandt, A., Singhal, S., & Pascuzzi, R. (2019). Art Therapy in the Management of Neurology Wellness and Burnout-A Pilot Study (P3. 9-079)

15. Tjasink, M., & Soosaipillai, G. (2019). Art therapy to reduce burnout in oncology and palliative care doctors: a pilot study. International Journal of Art Therapy, 24(1), 12-20.