A red flag is a detail in a patient’s story, a finding on physical exam, or a test result suggesting a serious condition worthy of unusual attention. From the early days of medical school, we are taught to identify red flags, like finding Waldo in the picture puzzles. Red flags highlight an ominous diagnosis. Without red flags, we miss the opportunity to save lives or make patients feel better. Amy Nau’s doctors were missing red flags.

Red flags first show up in the basic question: “What brings you in today?” Amy’s story began in her mid-thirties with a headache. She is a dental hygienist with a small child, and she developed headaches that did not get better with typical over-the-counter medications. Amy was frustrated, but she continued to go about her busy life, hoping that the headaches would just go away. Instead, the headaches got worse, and she was having difficulty at work. Lying in bed with the lights off in a quiet room was the only thing that that alleviated her head pain, and she was sent by her primary care physician (PCP) to see a neurologist for migraines. Amy was also diagnosed with anxiety and depression and started on a cocktail of medications that provided little relief. She was falling behind at work because of constant, blinding headaches that also took a toll on her personal life, but Amy continued to persevere, hoping that things would get better believing the medicine just needed time to work.

The next red flag was amenorrhea. After months without a period, Amy saw her gynecologist. Time after time, pregnancy tests were negative; the nurses at the gynecologist’s office began to consider Amy a “regular.” Weeks went by with ever-worsening headaches until another red flag shot up: Amy developed galactorrhea in addition to her amenorrhea. Another round of visits to her OB/GYN, PCP and neurologist were unrevealing, and she was continued on her medication regime with minor adjustments. Now, nearly a year and a half after her headaches started, she still had no explanation for her symptoms. Amy was frustrated and desperate for an answer; she worried she would never get her symptoms under control. She contemplated hurting herself as she had no desire to live with this constant pain. Fortunately, a chance interaction steered her course in a different direction.

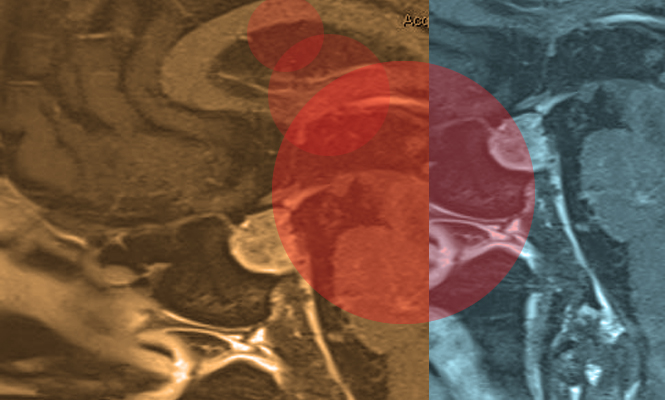

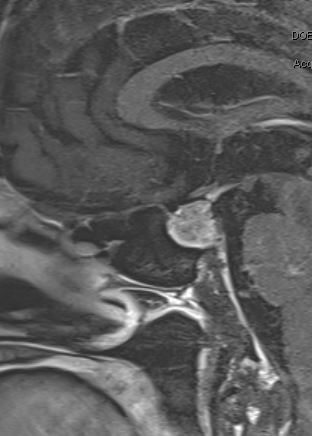

Amy’s husband, Jeff, is a house painter and was working at a local physician’s house. Upset and confused that his wife was continuing to suffer, Jeff struck up a conversation with the doctor to pass the time, in the hopes of any helpful insight into his wife’s condition. This doctor listened, recognized some of the red flags, suggested a number of new possible diagnoses and offered to see Amy in clinic. Surprised by this doctor’s attention to detail, empathy and willingness to listen, Jeff suggested that Amy seek a second opinion. Amy felt like she had nothing to lose so went to see the PCP in short order. After a battery of tests, including an MRI of the brain, Amy was diagnosed with a pituitary tumor. As scary as the diagnosis was, Amy was relieved and thankful that she had an answer about the source of her suffering. Amy’s doctor referred her to the pituitary program at the University of Rochester (UR), and as Amy was preparing for her upcoming visit, another random interaction added a further personal dimension to her case.

treated Amy Nau.

Jeff was working on another painting project when small talk led to the revelation that he was working at the house of Ed Vates, MD, PhD, FAANS, a skull base neurosurgeon, the surgical director of the UR Medicine Pituitary Program and the neurosurgeon Amy was scheduled to see. At her office visit, Dr. Vates explained that she had a prolactinoma. He explained to her the reason for her galactorrhea and amenorrhea. They spent the remainder of the visit discussing the various options, and after extensive discussion with Dr. Vates and the endocrinologist, Amy agreed with the recommendation of medical management. Unfortunately, Amy experienced significant side effects from both cabergoline and bromocriptine, and after another consultation with Dr. Vates, she decided to proceed with endoscopic pituitary surgery.

Amy recalls that the night before surgery, the personal relationship she and her husband had formed with Dr. Vates took the edge off the fear of impending brain surgery. The time arrived, and she was transported to the operating room where she underwent endoscopic resection of her tumor. The surgery went well, and she remembers waking up in the recovery room with Dr. Vates and her husband at her bedside. After surgery, she quickly returned to work as a dental hygienist. Her headaches gone, Amy felt like she had her life back, and both Amy and Jeff were ecstatic when shortly after surgery they were able to conceive another child. Amy is currently several years out from her surgery; she is happy and continues to do well, working and raising her family.

Amy’s story provides important lessons for physicians. The red flags that stand out in retrospect offered opportunities to pursue further testing or to listen more carefully to her story and her complaints. The goal of retelling her story is not to point fingers or criticize our health-care system. Instead, it is an opportunity to remind ourselves of the human side of medicine. As providers, it is vital to take the extra moments to listen to what a patient is saying. Amy felt one reason for the extended delay in her diagnosis was being unable to communicate her story or to participate in the potential solutions. She felt rushed and ignored in her office visits. It took a chance encounter outside of the health-care setting to change the trajectory of her story. Moving into the era of digital medicine, we need to heed the lesson of Amy’s story. We must empathize with our patients, take time to listen, communicate, ask more questions and move beyond the checklist. We must keep the art of medicine a thriving part of neurosurgical practice. We have to create the space that lets us see the red flags.

[aans_authors]