Editor’s Note: To read another perspective on measuring patient satisfaction, read “Point: Patient Satisfaction Surveys: Measuring Patient Contentment with Health-care Service, Not Quality and Value of Neurosurgical Care.”

There are few things that the federal government has built, or required of us in practice, that have actually improved health care and reduced costs while proving to be functional and efficient. However, one of the latest tools, known as Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) may break that mold if implemented in a meaningful manner. The intent of the HCAHPS initiative is to provide a standardized survey and methodology for assessing patients’ perspectives about the care that they have received. That’s the intent, and the jury is out if the intent will actually translate to meaningful data that can be used by practices to improve health-care delivery.

Creating Pertinent, Quantifiable Survey Questions for Patients

Obtaining surveys about medical practice was generally not common or consistent before HCAHPS, and therefore, it is not surprising that it is being met with resistance and mistrust. Surveys, however, are not foreign to businesses outside of medicine. Many restaurants implement surveys as a means of assessing the quality of service delivered to customers. They then “crunch” the data in a way that helps them build market share by improving their customers’ experience. The key to successfully obtaining survey data really boils down to ease of use, writing pertinent questions that are quantifiable and offering some kind of incentive. If, after going for a cup of coffee at a local shop, I was given a survey, I would decide if it was worth my time to fill it out. If the survey potentially took 20 minutes, I’d end it right there. If there were three questions, and I didn’t have to go online to do it, I’d likely complete the brief form even if it was only rewarded with a small incentive, such as a coupon.

The implementation in medicine should be very similar. Without some sort of incentive, the responses are likely to be very limited, and most often largely weighted toward patients who felt they had an extremely poor experience. Patients who felt their care was good might recommend the provider to friends, but likely would not fill out a cumbersome survey. Patients with less-than-ideal experiences might come back, or might search for another provider, but likely wouldn’t waste their time completing a survey about that practice for which they didn’t have a strong opinion. Thus, an incentive should be considered beyond “improving health care.” My suggestion would be to offset a nominal part of the copay pertaining to the particular visit being surveyed, and then incorporate the survey as a part of the exit instructions. The patient would complete the survey before leaving the facility and answer questions that pertain to the services rendered. It must also be reinforced to the patients that their responses are completely anonymous.

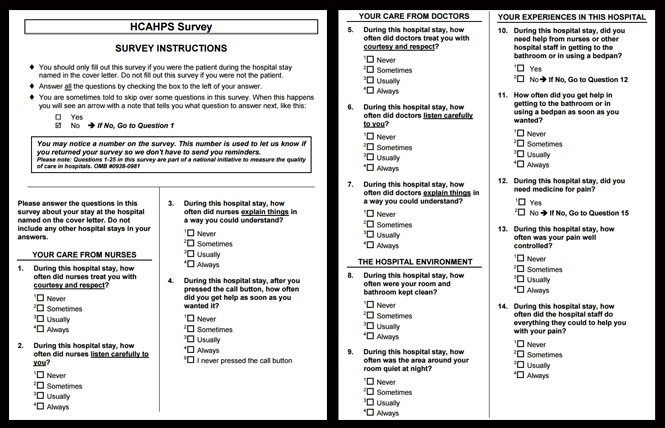

The types of questions asked may be practice-type specific. Some questions geared to patients with psychiatric illness may not be relevant to spine surgery, while others may have considerable overlap. Examples of overlapping questions could be: “Was it easy to get an appointment in this clinic?” with the follow-up question, “What were the barriers to getting an appointment in this clinic?” All with a series of check boxes that would allow for standardization amongst neurosurgeons and other specialty or primary providers. The differences in responses, however, should be specifically adjusted for the specialty being evaluated and the market in which the practice is located.

Real-world Practicality Through Granularity of Data

Thinking that psychiatry, neurosurgery and primary care could all be evaluated on equal footing with the exact same questions is unfounded and wishful at best. However, evaluating providers standardized for demand and services rendered is actually very realistic. Using the above “barriers question” example, if there is high demand in a particular market, but a limited supply of physicians to address that need, access necessarily becomes more difficult. That shouldn’t pop up as a red flag for the practice or physician, but rather, should demonstrate a greater need for more providers of that specialty in that general region. There is a real-world practicality in this information. Used correctly, the data provides an opportunity for patients to see how a specialist is rated against same-specialist peers. Similarly, specialists can find opportunities for markets in need of their services using HCAHPS data to map supply and demand.

Granularity and relevance of HCAHPS data becomes even more special when same services, regardless of specialty board, are evaluated for a particular physician. For example, a neurosurgeon may have exceptional outcomes and HCAHPS results with respect to their spine practice, when compared to the spine practices of other neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons locally and nationally. However, that same neurosurgeon may not perform as well as peers who practice vascular neurosurgery. Therefore, as a consumer, patients might request one neurosurgeon for cervical spine surgery while trying to see another neurosurgeon for their carotid stenosis. Getting even more granular, it would be possible to see a neurosurgeon’s results for a particular type of spine surgery at one hospital versus another hospital where that same neurosurgeon practices. This might help patients determine not only who their provider will be, but also the location where they feel that their needs would better met.

While the thought of a publicly-recorded survey is daunting, the implementation of the collected data is what should be of greatest concern. How the data is presented is far more important than the raw data itself. Allowing for specialty-specific questions to improve granularity, and relating collected data amongst peers performing the same services, regardless of board certification, is really where the value of HCAHPS will be. We must keep in mind that surveys can substantiate our hard work, show a need for our services and help us learn what we can improve upon to build our practices. In that frame, we can use this data to be more successful. We must also collectively help craft the presentation of the HCAHPS data so that patients reviewing it know what it actually means. An informed consumer will have more realistic expectations and can participate more effectively in his or her care.

[aans_authors]