The synergy of human and machine has been a topic of fascination for decades, with brain computer interfaces (BCIs) being at the cusp of the present wave of innovation. As these have progressed from research and development in the neural prostheses field to clinical adoption of therapies, the technological and clinical foci have primarily been on the restoration of neurological function. Effects, both intended and unintended, have been found at the personal and at the societal level after chronic implantation of these devices. As neurosurgeons, it is important to be cognizant of these effects since we may be involved early in the trial design as well as patient selection, consenting and care.

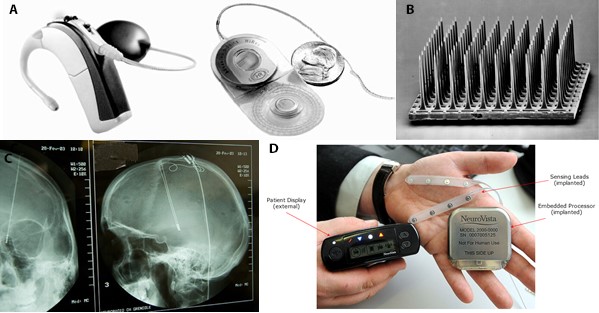

An early example of such a neural prosthesis is the cochlear implant. Revolutionary in its provision of hearing to many deaf patients, this device was initially soundly rejected by some in the deaf community due to the threat that it posed to the social dynamics and identity of the community. Such concerns included the notion that acceptance of a cochlear implant was admission that deafness was a disability and that early provision of hearing to prelingual deaf children may remove them from the deaf and sign language communities, thereby isolating the patients and contracting the communities.1,3,8 Fortunately, the best interests of patients and families persevered, and the viability of the communities was preserved.

Multichannel chronic neural recording devices with closed-loop outputs in the form of electrical neural stimulation or patient advisory signals have shown clinically significant benefit in the treatment of epilepsy and represent a first wave of low channel count BCIs.2,5,7 A new field has emerged that focuses on the ethics and effects on patient identity resulting from chronic implantation of neuromodulation and neural augmentation systems, including BCIs, and recent studies have generated fascinating results,6 with implications on patient selection and consent as well as device and trial design.

Expanding upon the first-in-man study conducted by NeuroVista on its Seizure Advisory System (SAS),2,4,5 investigators recently conducted detailed in psychological evaluations of a subset of these patients,6 bringing a new awareness of desirable and undesirable effects of such chronic monitoring and providing some insights into potential effects of next generation BCIs. Gilbert performed intriguing studies on the impacts of this “Intelligent BCI,” as he termed it, on the patient’s perceptions of self-change.6 In the FIM study involving 15 patients, a 16-channel chronic BCI, or SAS, was implanted in patients with medically refractory epilepsy. The SAS performed chronic monitoring of ECoG signals, calculated a customized combination of personalized features from these signals and, after a training period, used this information to generate an estimate of seizure likelihood for the patient.5 The SAS provided real-time notification to the patient of his or her likelihood of having a seizure, and this was displayed by the illumination of one of either a red, white or blue LED, denoting a high, intermediate or low risk of seizure, respectively, as well as via an audible and vibratory alarm.2 This information allows patients to initiate preventative or therapeutic actions, such as sitting down or laying in a safe place or taking a fast-acting AED.

In a detailed in-person psychological assessment performed by Gilbert on six of the 15 implanted patients in the NeuroVista SAS study, the majority (four of six) patients described anticipated findings of an increased sense of control and empowerment from the device saying, “I felt more in control when I used the device” and “[The BCI] gave me more confidence.”6 In one patient, the unanticipated effect of feelings a loss of control and distressing changes in patient identity were found.6 These findings may be related to preoperative beliefs and identities of the patients, and as such, may be helpful in patent counseling as well as in patient selection.

One patient who had a frank understanding of the negative effect of epilepsy on her identity described a powerful positive effect with the SAS BCI device. Regarding epilepsy, she stated, “It has caused me a lot of depression, anguish and a lot of teasing.” Regarding the BCI, she stated, “it follows you through the shower and everywhere and it becomes part of you. Because that’s what it did, it was me, it became me … with this device I found myself.” The impact on her identity was profound, described as, “It changed who that person was then and I found myself changing … growing I suppose, and it changed my confidence, it changed my abilities – it changed how stressed I was, how well I slept, then I could make decisions without having to worry about what might happen. With the device, I felt like I could do anything – I can do everything I want to do. I was more capable of making good decisions – not bad decisions – because there’s been times where I’ve made bad decisions. I can bake safely, I can shower safely. So it gave me a new lease on life and nothing could stop me.”6

One patient described a markedly different experience, which seemed to correlate with a very different handling of her pre-implantation experience with epilepsy, which she described as, “I just kind of pretended that it didn’t really exist. I didn’t see myself as an epileptic.” Implantation of the SAS BCI was an admission of having epilepsy and despite receiving potentially helpful predictive information regarding seizures, the experience was very distressing to the patient, who stated, “[The BCI] made me feel like I was just sick all the time. … It also made me feel like I was different to everyone else.” The scope of her increased distress was well characterized by her statement, “I felt so weird all the time; before it, I only felt strange having the seizure.” Consequently, her sense of self was affected, as she expressed, “It made me feel like I had no control. I got really depressed. I had been depressed before, and I knew what depression was.”6

These fundamentally distinct patient experiences were described by patients with very different preoperative views and mechanisms for handling their epilepsy. The patient who accepted – though disliked – the condition had an extremely positive experience with seizure prediction from the SAS device; however, the patient with preoperative denial had a distressing experience.

These early studies on the psychological impact of neural implants are enlightening and further consideration of these effects in future BCI and neural implant studies may be helpful in trial design, patient selection and patient counseling.

References

- Christiansen JB, Leigh IW. Children with cochlear implants: changing parent and deaf community perspectives. Archives of Otolaryngology — Head & Neck Surgery 2004;130(5):673-677.

- Cook MJ, O’Brien TJ, Berkovic SF, Murphy M, Morokoff A, Fabinyi G, et al. Prediction of seizure likelihood with a long-term, implanted seizure advisory system in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy: a first-in-man study. The Lancet Neurology 2013;12(6):563-571.

- Crouch RA. Letting the deaf be deaf. Reconsidering the use of cochlear implants in prelingually deaf children. The Hastings Center report 1997;27(4):14-21.

- DiLorenzo DJ. Neurovista: Concept to first-in-man: The war story behind launching a venture to treat epilepsy. Surgical neurology international 2019;10:175.

- DiLorenzo DJ, Leyde KW, Kaplan D. Neural State Monitoring in the Treatment of Epilepsy: Seizure Prediction-Conceptualization to First-In-Man Study. Brain Sciences 2019;9(7):01.

- Gilbert F, Cook M, O’Brien T, Illes J. Embodiment and Estrangement: Results from a First-in-Human “Intelligent BCI” Trial. Science and engineering ethics 2019;25(1):83-96.

- Morrell MJ, Group RNSSiES. Responsive cortical stimulation for the treatment of medically intractable partial epilepsy. Neurology 2011;77(13):1295-1304.

- Tucker B. Deaf Culture, Cochlear Implants, and Elective Disability. Hastings Center Report 1998;28(4):6-14.