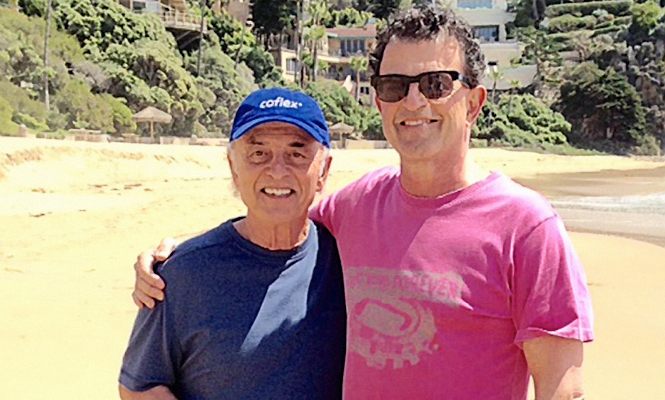

In conjunction with Neurosurgery Awareness Month, observed August 2015, AANS Neurosurgeon interviewed two sibling neurosurgeons, Jacques Palmer, MD, FAANS(L); and Sylvain Palmer, MD, FAANS, for their perspectives on their chosen profession, what influenced them and how they might have influenced each other, and what their lives are like both in and outside the operating room. We share the conversation with you here:

Please describe your training, as well as provide a brief professional overview and where you’re currently practicing.

Jacques J. Palmer (JP):

University of Michigan Medical School, 1961-65;

University of Washington Hospital Internship, 1965-66;

University of Washington Medical Center Neurosurgical Residency, 1966-70; Postgraduate training at Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, England, 1970-71, with Joe Pennybacker, FRCS, who exhibited extraordinary clinical acumen; and Micro-neurosurgery training, Kantonsspital, Zurich, 1972, where I developed a life-long interest in the operating microscope and microsurgical techniques. For more than 40 years, I have been in private practice in Mission Viejo, Calif., where I was instrumental in the creation of a regional trauma service. My brother and I participated in the development, refinement and teaching of micro-neurosurgical techniques of the spine. Currently, I am semi-retired, assisting in the OR and lecturing on spine-related topics.

Sylvain Palmer (SP):

I did two years of undergraduate work at Cornell University. I then transferred to the Johns Hopkins University and Medical School where I obtained my BA and MD degrees. I stayed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital for my neurosurgical training. I later joined my brother in practice in Mission Viejo, Calif., where I have practiced ever since. I am currently in a six-man neurosurgical group, Orange County Neurosurgical Associates.

What attracted you to a career in neurosurgery?

JP: Initially, I was attracted to psychiatry because of the mystery of the function of the brain, but I missed the physical and technical component. Neurosurgery was the perfect combination of thinking, discovering and surgical skills applied to the care of patients.

SP: I was attracted to a career in neurosurgery by the shear magnitude of the profession. It stood out to me as the pinnacle of achievement in medicine. It met my personal and family requirements for intellectual accomplishment. My family was very education-oriented, and both my brother, Jacques, and I went into neurosurgery, and my sister, Nathalie, went into dentistry. Nathalie would bring home the skeleton skull, and I would study it with her. When she was interviewed as the first women to be admitted to the University of Michigan Dental School, I was asked what I wanted to be when I grew up. I was 10 years old at the time and told the interviewer I wanted to be a brain surgeon. On a less serious note, the Ben Casey television show idealized what being a neurosurgeon could be like, and I never missed as episode.

What neurosurgeon (living or deceased) most influenced your career and why?

JP: Arthur A. Ward Jr., MD, chaiman of the University of Washington neurosurgery department, had a calm and thoughtful demeanor about him. He also demonstrated great technical skills even before the use of the microscope and other current neurosurgical techniques. Basil Harris, MD, FAANS(L), attending neurosurgeon in the department of neurosurgery, University of Washington Medical Center, introduced new ways of operating, which showed me that there are “other ways” of doing things. This continued throughout my neurosurgical career.

SP: The neurosurgeon who most influenced me before entering training was Harvey Cushing. No surprise there. He was a renaissance man. One of the reasons I chose to attend Johns Hopkins was because of Cushing’s association with Hopkins. In training, each of my professors had their own hand in shaping me, but I would be remiss in not pointing to Donlin Long, MD, PhD, FAANS(L), a gentleman and a born teacher, who set the tone for the entire department.

What is it like to have two neurosurgeons in the family? How has your brother influenced your career?

JP: It made our parents, particularly our mother, very proud, having emigrated to the U.S. from Europe after surviving WWII. They were also proud of my sister, Nathalie, who was a year younger than I, and was the first woman to graduate from the University of Michigan dental school. My sister and I were at the University of Michigan at the same time, she in dental school, I, in medical school. Unfortunately, she died at an early age.

While [my brother and I] were actively sharing an office, the frequent interactions about challenging patients helped us find the “right thing to do.” As a much-younger neurosurgeon, my brother helped me keep current. Since I became semi-retired, I very much enjoy assisting him in the operating room on a regular basis. I also assist my younger colleagues, which gives me an opportunity to share my many years of clinical experience.

SP: My brother, Jacques, is 13 years my senior, and anything he did was a major influence on me. I wanted to be just like him, though that seemed an impossible-to-attain dream, at least, according to our mother. I would even pick my glasses frames to match the ones he was wearing. Professionally, the opportunity to work closely with him probably was the major influence in my deciding to pursue private practice and not academics. It has not been a disappointment, and it has been a constant support and comfort to have him by my side personally and professionally. That is not to say that we did not have our big brother/little brother moments. I think I was about 50 before I stopped being referred to as Jacques’ little brother.

What was your fondest memory from your residency?

JP: One evening, after a party, Dr. Ward asked me if I would like to go for a ride in his Jaguar sports car. His wife told him to be sure and let me drive. That moment remains a fond memory, particularly since he is gone.

SP: The intellectual and physical demands of residency were balanced by the support I obtained from everyone involved in the process. That included not only the professors and fellow residents but also the nurses and other staff who made surviving residency possible. Spending one summer working in the animal lab with Vivian Thomas was a particular treat. I can’t forget suntanning on the roof of the Halsted building, which was accessible from the 14th floor neurosurgery offices. I also have pleasant memories of learning to sail on the Baltimore inner harbor before it was gentrified.

What career advice would you give to a neurosurgeon just starting in the profession?

JP: Completion of the training program is only the beginning of a neurosurgeon’s journey. Keeping an open mind and learning from others how they solve problems will make the field forever fresh and exciting.

SP: I would advise anyone considering a career in neurosurgery to take the time to appreciate each stage of the development process. The goal is to be a capable human being as well as a capable neurosurgeon. The patients demand much more of you than your technical skills. I often jest that the three most important courses I studied and that I continue to use today as a neurosurgeon were psychology, typing and wood-shop.

What would you consider to be your top three professional accomplishments?

JP: 1. The use of prophylactic antibiotics at a time when the practice was severely criticized by many medical colleagues but has now become standard practice.

2. The use of craniectomies for brain decompression in severe head injuries at a time when few neurosurgeons advocated such techniques, well before the advent of trauma centers and ICP monitoring.

3. Advocating the use of the operating microscope and minimally invasive surgical techniques, particularly as relating to the treatment of spine conditions.

SP: I am most proud of my work in two areas. The first is multimodality monitoring of critically head injured patients. In particular, it was the addition of parenchymal oxygen monitoring that revolutionized our care of patients with severe TBI. We then went on, with the philanthropic support of the Williams family, to train more than 50 other centers interested in adopting multimodality monitoring in their institutions as part of the Adam Williams Traumatic Brain Injury Initiative.

The second was the development of techniques for the minimally invasive treatment of spinal disorders. The minimally invasive treatment of spinal stenosis offers the elderly, who might otherwise not be candidates for surgical treatment, the ability to maintain or regain their mobility — a key to continued quality of life.

Lastly, I have enjoyed mentoring others in their career development. Advanced practice nurses are making a significant impact on our practice of neurosurgery, and my involvement with the careers of Mary Kay Bader and Linda Littlejohns will always be a highlight for me.

How has the specialty of neurosurgery changed the most significantly since you began practicing?

JP: Increasing reliance on imaging techniques and the use of ever-changing surgical instrumentation.

SP: In my early career, the practice of neurosurgery required much more detective work and the ability to make decisions from very limited information. The availability of advanced imaging and stereotactic guidance has forever improved are ability to care for our patients. Also, neurosurgery has put on a much more of a human face in recent years with the current graduating neurosurgeons interested in family, business and outside activities much more so than was possible in years past.

If you could not have been a neurosurgeon, what other career would you have chosen?

JP: In high school, I was interested in nuclear engineering, but shortly after starting college, I became more attracted to the social sciences, humanities and biology. I graduated from the University of Michigan with a double major in cultural anthropology and zoology.

SP: I have always been interested in architecture. I think that would have been a very satisfying career, except for my total lack of artistic talent.

What interests do you have outside the OR?

JP: I play the saxophone, which is more practice than play. We moved to live in a golfing community as I was approaching “retirement.” Unfortunately, I started playing much too late in life to be good at it, but I enjoy playing a few holes most of the days.

I enjoy “fixing things.” The house requires constant attention from audio and electrical to plumbing and gardening. I am constantly solving problems and using my technical skills in more mundane endeavors.

SP: My interests outside of the OR mainly revolve around family. I am painfully aware of how the demands of my early career in neurosurgery kept me from being a fully engaged participant in the family. Today, I never miss an event, and there are plenty of activities to attend with three children in college and all three playing D1 sports.

What else would you like the neurosurgical community to know?

JP: It has been a great blessing for me to have a younger brother as a colleague and an associate. I am proud of the professional he has become and the warm, caring human being he is as a husband and father of three beautiful and very gifted children.

[aans_authors]