Editor’s Note: Dr. Deborah Benzil has served as Editor of the AANS Neurosurgeon for five years. As her term concludes, she elected to use her editorial for the theme World of Neurosurgery to reflect on her own world of neurosurgery. In Part 2, she explores her post-residency career. Read Part 1

Early Career

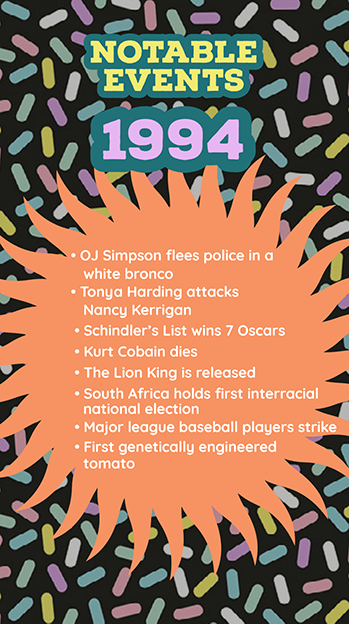

In 1994, the concept of a two-career family was still rather atypical. We faced the daunting task of finding simultaneous jobs and taking care of two young children with only remote family support, while fulfilling our ongoing work responsibilities. Entering practice at that time also involved confronting a medical world in rapid transition. Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) were gaining force, leading to dramatic reduction in physician reimbursement. Medical malpractice cases were rising, leading to an astronomical increase in rates. Medical school deans were locked in battle with both hospitals and physicians for control of authority and money. In addition, nothing in residency really prepares you for life after. Up to that point, our lives had been relatively linear and predictable – high school, college, medical school then seven years of residency. Life was scripted and mostly dependent. Then, overnight everything flips. Unfortunately, the transition today has changed little from then – accounting for the incredibly high rate of job changes within the first two years (nearly 50%).

In 1994, the concept of a two-career family was still rather atypical. We faced the daunting task of finding simultaneous jobs and taking care of two young children with only remote family support, while fulfilling our ongoing work responsibilities. Entering practice at that time also involved confronting a medical world in rapid transition. Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) were gaining force, leading to dramatic reduction in physician reimbursement. Medical malpractice cases were rising, leading to an astronomical increase in rates. Medical school deans were locked in battle with both hospitals and physicians for control of authority and money. In addition, nothing in residency really prepares you for life after. Up to that point, our lives had been relatively linear and predictable – high school, college, medical school then seven years of residency. Life was scripted and mostly dependent. Then, overnight everything flips. Unfortunately, the transition today has changed little from then – accounting for the incredibly high rate of job changes within the first two years (nearly 50%).

On a personal level, I struggled with finding the right balance during this period. The pressure to grow a practice, gain academic credentials and compete “with the boys” conflicted significantly with my concept that my post-residency years would provide me reliable time for my family and attention to my own personal health (which I had sorely neglected for years). This was further complicated by the first wave of global health care transitions and turmoil within my department. Predatory individuals were all too common in neurosurgery in those days, and junior faculty/staff were too often the victims of unethical practices. Neurosurgery practices and departments were lucrative and powerful, making those at the top nearly untouchable. The most important lesson learned was the power of the patient: if you do the right thing and care for your patients, they will become your top marketing strategy. A constant demand for your services gives you power and relative security when the world around you is faltering.

Out of the Ashes

If what life gives you is lemons, as the saying goes, then make the best damn lemonade in the world! In the years that followed, I discovered that I had no trouble building and sustaining a practice, and this became a valuable asset. I learned quickly that I had to be willing to learn new techniques and add to my surgical repertoire. This included mastering spine instrumentation (a rapidly growing demand), minimally invasive techniques and embracing innovation, particularly through the establishment of a spine radiosurgery program.

In addition, I swiftly learned how important the “business of neurosurgery” is and applied myself to acquiring expertise with the same fervor I had devoted to learning surgical technique and patient care. This ultimately led me to take on roles within organized neurosurgery that were rewarding, complementary and provided a tremendous springboard for leadership positions. Widening my professional circles was invaluable on every level. My increasing visibility allowed me to begin to mentor and support the marvelous generation of women and forward-thinking men in training and starting their own careers, during equally tumultuous times in medicine.

My initial academic position at New York Medical College evolved to a wonderful period on faculty at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, where I collaborated with the resident team to develop a comprehensive socioeconomic education curriculum. My clinical practice flourished and organized neurosurgery offered many leadership opportunities. Several years ago, I moved to the Cleveland Clinic to take the position as vice chair of neurosurgery. Here, I continue patient care, but have increased opportunity to teach and train an outstanding resident team as well as apply the strategic and leadership skills honed throughout my career. For the most part, I now feel I have a good balance between work, family, friends and my own needs.

The Bulletin, née AANS Neurosurgeon

The Bulletin (1992) emerged from the ashes of the AANS Newsletter (started in 1972) under the editorship of Michael Apuzzo, MD FAANS(L). He helped craft a quarterly publication that included news, announcements and a few select pieces from the president and other neurosurgical leaders. A short list of remarkable editors followed, each adding critical elements toward what stands today as a highly visible and accessed online publication:

- John Popp, MD, FAANS(L): Enhanced socioeconomic content, style and departments.

- William Couldwel, MD, PhD, FAANS: Initiated “themed” issues, expanded scope and breadth of content, introduced peer-reviewed component and department editors.

- Michael Schulder, MD, FAANS: Ushered in the online era in 2010, garnered numerous awards for the now mature and wide-reaching publication.

My world on the editorial board started in 2005, through appointment by Fremont Wirth, MD, FAANS(L), – a good fit for my skills and interest. Over 15 years, the publication has matched the growth and evolution of neurosurgery and technology. There have been amazing staff who have supported this project and dedicated neurosurgical volunteers whose art, poetry, writing and depth of knowledge make it soar. Today, there is a cadre of young, enthusiastic members with a vast supporting network of students, residents and colleagues who have crafted a continuously evolving online publication that serves as a tremendous resource for neurosurgeons. This work stands as one of the real highlights of my personal involvement in organized neurosurgery.

Women in Neurosurgery (WINS)

Today women represent half of all medical school classes and have finally surpassed 15% of entering neurosurgery residents. Within my world of neurosurgery, the evolution of women neurosurgeons in numbers, acquisition of leadership roles and acceptance is as significant as any of the technological innovations. Thor Sundt, MD, hosted the resident luncheon 1989 in Atlanta during the CNS meeting. WINS was launched after a small number of women residents sat together during this luncheon. It was the very first time I had spent time at a neurosurgical event with more than one other woman! The collection of three females naturally attracted several others after the talk and, as they say, the rest is history. Many women declined early involvement in the organization out of fear of retribution. In fact, I kept my own leadership role a secret so effectively that nearing graduation, my chair forwarded information he thought I might find helpful about a growing organization for women neurosurgeons.

Women have and continue to transform neurosurgery in many traditional ways, such as through:

- Scientific research and innovation;

- Clinical and technical excellence;

- Teaching and education;

- Leadership and administrative skills; and

- Socioeconomic, advocacy and fiduciary expertise.

Because women challenge the status quo, ask different questions, provide alternative perspectives and think differently, we have added uniquely to the continued growth and success of our specialty. While working on The Bulletin/AANS Neurosurgeon represents one highlight of my career in organized neurosurgery, being a part of the evolution of WINS as well as working with individual female neurosurgeons takes pride of position. They are my dear friends, my sisters-in-arms. Today’s generation will carry the torch to places I could not dream of in 1983 when I began, in 1994 when my academic career began or even today as I savor the last years of my long career.

And in the end…

The Beatles sing, “And in the end, the love you take, is equal to the love you make.”

My days in the world of neurosurgery are not done but my 15+ year stint with The Bulletin/AANS Neurosurgeon ends with this issue. This world of neurosurgery has witnessed (to name a few) the birth and growth of MRI, stereotactic radiosurgery, aneurysm coiling, complex and minimally invasive spine, functional interventions and neuro-critical care. It has also weathered multiple periods of healthcare reform, economic transformation of healthcare systems, substantial changes in resident education and enormous growth in the administrative and regulatory aspects of medical education and delivery. Residents are millennials or beyond, technology has advanced, knowledge is said to be doubling every 12 hours and the world is much flatter. Tomorrow’s world of neurosurgery has the potential to positively impact patients through change that we cannot yet imagine. Perhaps, somewhere there is an undergrad or a medical student who will encounter a 16-year-old trauma patient, or an elderly tumor patient, or similar, whose world will tilt as mine did decades ago.

[aans_authors]