Mini-craniotomy for Subacute Subdural Hematoma

Case Description

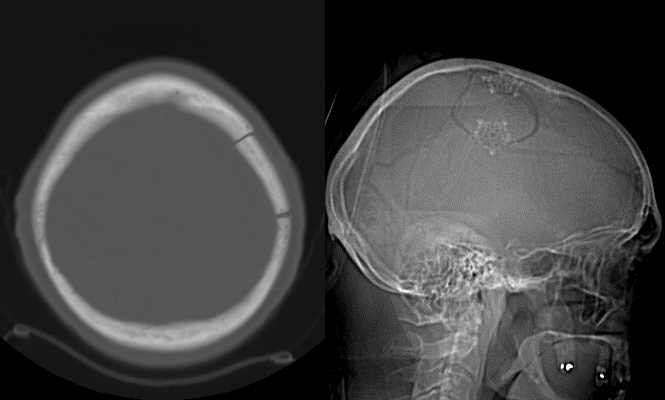

This 82-year-old, right-handed Caucasian gentleman on treatment for hypertension and hyperlipidemia presented with one day of right side facial, arm and leg weakness and slurred speech. On exam, the patient had dysarthria with right upper extremity weakness. The rest of his neurological examination was normal.

[aans_poll id=”4487″ view=”prompt”]

Discussion

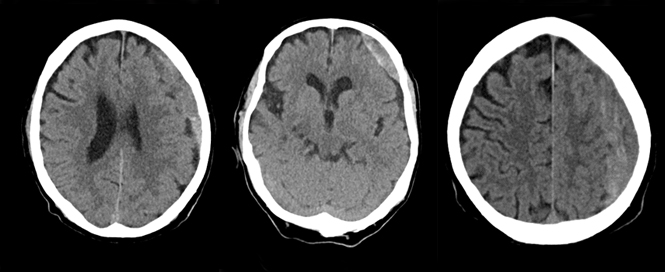

Subdural hematomas (SDH) not associated with significant traumatic brain injury (TBI) most commonly occur due to blood accumulation around a superficial parenchymal laceration or tearing of bridging veins or cortical arteries during acceleration-deceleration accidents. They may be more common in patients using anti-platelet or anti-coagulant agents. Once formed, they progress through three phases. First, an initial acute phase (one to three days) occurs during which the clotted blood in the subdural space is thick and electron dense; this appears hyper-dense on non-enhanced CT scans. With time, the blood liquefies and loses its thickness and density entering a sub-acute phase (four days to three weeks). At this point, it appears iso-dense to the brain parenchyma. It eventually enters a chronic phase (>3 weeks) wherein in which the hemorrhage appears hypo-dense to brain parenchyma on non-enhanced CT scans.

Simultaneously, an inflammatory response provoked by the hemorrhage causes a migration of fibroblasts to the clot within days. These contribute to the formation of membranes that surround and segregate the clot. These membranes also provoke genesis of relatively exuberant but immature and fragile capillaries that vascularize the membranes but also contribute to clot expansion through multiple minor subclinical hemorrhages. The end result is a clot with septations that are best seen on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The other major concurrent event is a progressive fibrinolysis of the hematoma itself that leads to the classic “motor oil” consistency and appearance of a chronic SDH.

Any SDH (even without parenchymal injury/edema) causing significant mass effect, shift of midline structures with subfalcine herniation or effacement of basal cisterns with uncal or transtentorial herniation requires surgical intervention, particularly in a patient with neurological symptoms or signs that are concordant with the imaging findings. Asymptomatic patients with a SDH not causing significant mass effect or neurological deficit may be treated non-surgically and are simply followed with serial cranial CT scans. Spontaneous resolution may sometimes be observed in these patients.

Among patients with a cranial SDH requiring surgical intervention, a chronic SDH without significant acute component may be effectively drained with burr holes alone that are generally placed in frontal and parietal locations, especially if there are minimal septations or loculations (1). Acute SDH with a volume of more than 25-30 cc may require a larger craniotomy via a traditional reverse question-mark scalp incision and myocutaneous flap. Burr holes are generally placed in frontal, temporal and parietal locations and connected to elevate a large craniotomy flap that provides access to the entire hematoma and facilitates easy removal. Sub-acute SDH may have a consistency more viscous than chronic SDH but not as dense as acute SDH.

While burr hole drainage has been used to effectively treat these lesions (2), there can be increased amount of residual hematoma if it is not sufficiently liquefied. A question-mark incision with large craniotomy is another option in acute on chronic SDH – particularly if preoperative imaging demonstrates the presence of loculations and membrane formation in the hematoma. These membranes are less commonly seen in sub-acute hematomas reflecting the time required for their formation.

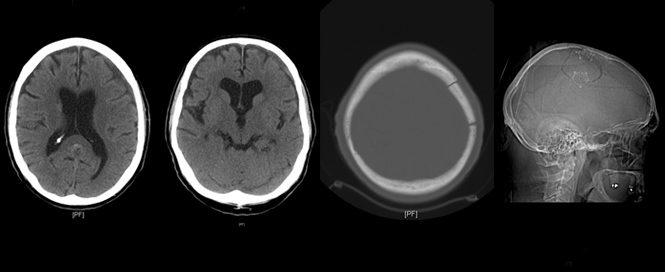

A mini-craniotomy centered in the middle of the SDH has been proposed in recent years (4). This cranial opening accords better visualization and access than simple burr-holes and is less extensive than a large craniotomy. There are purported advantages such as a linear incision suffices and obviates the need for a scalp flap and also heals well. The cranial opening is smaller but maintains access to the hematoma with direct visualization (4). We have used this in patients with sub-acute SDH that required surgical evacuation and have found it to be very effective with minimal morbidity and with shorter operating times than with a standard craniotomy.

With the patient supine under general anesthesia and the head elevated and turned to the contralateral side, we make a linear skin incision approximately 5 cm in length that is centered on the approximate midpoint of the hematoma. Two burr holes are made and connected elevating an approximately 4 cm diameter bone flap over the middle of the hematoma. The dura is opened in cruciate fashion and tacked back allowing the surgeon an unobstructed view in all directions along the convexity of the hemisphere. Access to the subdural space is excellent in all directions and evacuation of the hematoma is relatively straightforward with copious saline irrigation (3). Placement of a subdural drain, if necessary, under direct visualization is also facilitated and replacement of the bone flap and closure is rapid with superb healing.

[aans_authors]

THE EXPERTS WEIGH IN

Bizhan Aarabi, MD, FAANS, Baltimore, Md.

The mini-craniotomy recommended and tried by Drs. Ibrahim and Prabhu is also supported by the literature. The procedure is excellent for SDH and not recommended for an acute SDH, incompletely liquefied SDH, uncomplicated chronic SDH or acute-on-chronic SDH with membrane formation. For a fully liquefied, clinically significant subacute SDH, almost any surgical procedure works: percutaneous drain under local anesthesia, subdural evacuating port system (SEPS) drain under local analgesia, burr holes (one, two or three, small or large), mini-craniotomy or full craniotomy.

The mini-craniotomy recommended and tried by Drs. Ibrahim and Prabhu is also supported by the literature. The procedure is excellent for SDH and not recommended for an acute SDH, incompletely liquefied SDH, uncomplicated chronic SDH or acute-on-chronic SDH with membrane formation. For a fully liquefied, clinically significant subacute SDH, almost any surgical procedure works: percutaneous drain under local anesthesia, subdural evacuating port system (SEPS) drain under local analgesia, burr holes (one, two or three, small or large), mini-craniotomy or full craniotomy.

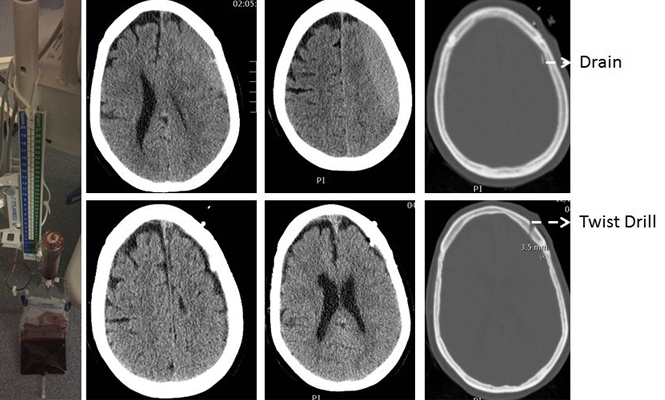

At the Shock Trauma Center at the University of Maryland, we routinely begin with a percutaneous drain under local anesthesia and if not successful in evacuating the hematoma, will proceed with craniotomy. The success rate for complete evacuation of a subacute SDH seems to be quite high. Considering that many of our patients have major co-morbidities and are on antiplatelet medications or anticoagulants, we think this is the procedure of choice. The procedure takes about 30 minutes start to finish, does not need general anesthesia and could be performed in the Trauma Resuscitation Unit (TRU) or Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Consent is obtained, one dose of antibiotic is given and the responsible nurse performs time out. If the procedure fails in situations such as partially liquefied clot, the next procedure is a full craniotomy.

Case report:

This 56-year-old woman was assaulted a month prior to admission. She was complaining of headache and right hand apraxia. She was alert and oriented in the TRU and an exam demonstrated only slight right pronator drift. Non-contrast CT scan revealed a moderate sized subacute SDH over the left convexity with effacement of the sulci and collapsed left lateral ventricle. A percutaneous subdural drain was placed in the TRU (a classic intraventricular cannula), and within four hours, the SDH was out. She was discharged the same day. Follow-up three weeks later in clinic did not reveal recollection of the hematoma.

Editor’s note: The case described above by Dr. Aarabi does demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of a percutaneous drain for the evacuation of a subacute subdural hematoma. The patient did well and was discharged the same day. However, this is not our customary practice. There is a risk of re-accumulation of a subdural hematoma or re-bleeding that is maximal in the first 12-24 hours; hence, our practice is to obtain a non-contrast CT head 12-24 hours after removal of a subdural drain and only discharge the patient if they are asymptomatic and neurologically intact with a stable CT showing no new intracranial pathology.

The staff of AANS Neurosurgeon and the entire neurosurgery community is saddened at the passing of a friend and colleague, Tarik F. Ibrahim, MD. Tarik passed away unexpectedly on July 30, 2016, at the age of 34. A neurosurgery chief resident at Loyola University Medical Center/Stritch School of Medicine in Maywood, Tarik had been accepted into a prestigious fellowship in skull base surgery at the Swedish Neuroscience Institute in Seattle. Please take a moment to remember and honor the memory of Dr. Ibrahim. He was an exceptional neurosurgeon and and outstanding individual, and he will be greatly missed. Our prayers and condolences are with his family.

The staff of AANS Neurosurgeon and the entire neurosurgery community is saddened at the passing of a friend and colleague, Tarik F. Ibrahim, MD. Tarik passed away unexpectedly on July 30, 2016, at the age of 34. A neurosurgery chief resident at Loyola University Medical Center/Stritch School of Medicine in Maywood, Tarik had been accepted into a prestigious fellowship in skull base surgery at the Swedish Neuroscience Institute in Seattle. Please take a moment to remember and honor the memory of Dr. Ibrahim. He was an exceptional neurosurgeon and and outstanding individual, and he will be greatly missed. Our prayers and condolences are with his family.

RESULTS FROM PREVIOUS GRAY MATTERS SURVEY

Topic: Treatment Options for Patient with MMD

[aans_poll id=”3503″ view=”results”]