Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is often called the epidemic of the West. The socio-economic impact and ubiquity is often recounted in the introduction in scientific articles to emphasize the relevance of the work presented. To make the magnitude of TBI more comprehensible, in the U.S., one person incurs a TBI every 21 seconds, and every five minutes, one person will die and another will become permanently disabled. Numbers are abstract. Even for neurosurgeons, it is difficult to grasp what having a TBI really means for a patient. This article tells a story of one TBI patient I encountered from my perspective as well as my patient’s, what she remembers and how it changed her life.

A Neurosurgeon’s Perspective

My resident called me around 7 p.m. about a patient in the emergency room. The patient was a 60-year-old woman who had been walking her dog when she got hit by a car. EMS reported the patient was hit at a speed of 30-35 MPH and was catapulted over the front of the vehicle causing her to strike the street with the back of her head.

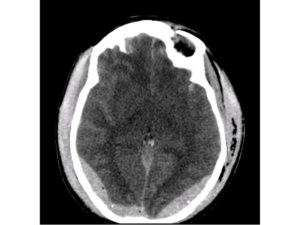

When EMS arrived, the patient was unresponsive. A head computed tomography (CT) taken in the trauma bay showed multiple closed occipital bone fractures overlying the transverse and sagittal sinuses. There was pneumocephalus and bilateral epidural hematomas crossing the midline, most likely from sinus bleeding, indicating injury to the sagittal or transverse sinus from the bone fracture (Figure 1).

This patient had to go to the OR. I positioned her prone, made a skin incision spanning her occipital bone fracture on both sides and planned a bilateral craniotomy to leave the bone that was over her sinus and evaluate the epidural hematomas. This would also give us access to repair any sinus injury that may have occurred.

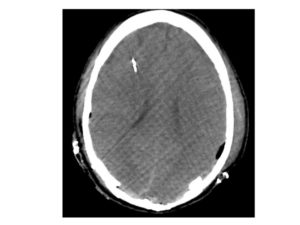

As is sometimes the case when a physician expects the worst, things turn out well. I was able to evacuate the epidural hematoma, elevate the skull fracture and repair the tear in the transverse sinus. The postoperative CT looked good, but the patient did not (Figure 2).

She would not wake up, and her Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) remained a 5. We placed an oxygen (O2) and intracranial pressure (ICP) monitor and fought her ICP over the next week. Her exam remained poor: no eye opening, flexion of the upper extremities, only a flicker in her legs along with continued support from a ventilator. Even when her ICP returned to normal, the patient did not wake up.

I had multiple meetings with the patient’s sister and other family members. Two mantras were going through my head: “There is an outcome worse than death,” and “You have to survive first before you can get better.” The patient was a science writer with a PhD. She enjoyed her independence and her work. How would her life look? What would she be able to do? These were the questions the family asked me. Why was she not waking up? She had an epidural; she should do well. Why did we have to fight the ICP for a week? What would I do if she were my relative? In the end, we decided to move ahead with a tracheotomy and feeding tube placement 10 days after her injury and would reevaluate our care goals if she did not to get better in a month.

Less than a month after she was discharged, I walked into the exam room to see her for a follow-up visit. I was surprised to see no stretcher. “Where is the patient?” I asked the woman, note pad in hand sitting next to the exam table. She replied, “I am your patient.” I was confused. Did I read the wrong discharge summary before I came into the room? Do I have the wrong patient? I confirmed her name and pulled up her records. There she was: my GCS 5 patient, my end-of-life discussion patient, looking up at me ready to take notes.

We all take care of TBI patients, and wins like these are why we do what we do. We all know many patients who do not have such a positive outcome; however, this is a cautionary tale not to be pessimistic and nihilistic as remaining positive when treating TBI patients can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy.

A Patient’s Perspective

Six months ago, on Feb. 16, 2016, I was struck by a car while finishing a walk with my dog, Buddy. While my memories of that evening still do not go beyond my decision to step out into the street, I have since learned that the driver stopped and remained on the scene and several neighbors came outside to help. Two stayed with me to wait for an ambulance, during which time I was mostly unconscious and bleeding. Buddy, who was driven to a Boston animal hospital by a kind man I did not know, suffered a badly broken leg. He underwent two surgeries and was temporarily adopted by his loving pet sitter. He has fully recovered and is back to long walks and the occasional rabbit chase. My injuries were more severe. I had a longer path to travel. With a fractured skull, severe TBI and a broken left humerus, I was admitted to the ICU at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center where I was put under the care of Martina Stippler, MD, FAANS.

As a molecular biologist, I have always strived for insightful thinking and clear communication. My primary tasks at work include understanding and writing about experimental data while helping to foster effective communication within our group of about 25. Some jobs require mostly brain and very little brawn, and this is one of them. I am also an avid runner and have completed over a dozen marathons. Unfortunately, my TBI put a huge roadblock on both my work and my exercise.

Notified either by my boyfriend, Joshua, or the hospital, my terrified family sprung into action, traveling to Boston from their homes in Ohio, Colorado, and Minneapolis; my sons from their universities in Amherst, Mass., and Washington D.C. The woman they saw bore little resemblance to the woman I was before that fateful night. My body had swollen an additional 35 lbs due to injected fluids (which slowly drained out of me over the next two weeks). My hair had been shaved, a ventilator had been inserted (it became a less-oppressive tracheal tube after 10 days), I had a terribly swollen and protruding tongue that had to be wrapped to keep moist, and my body was not fully in control of functions; in short, my family could hardly believe it was me. As my sister Susan (co-author of this article) tried to joke at the time, only my nose seen from the side gave me away. The fractured humerus, while very much secondary to my bigger problems, was the only thing my family could really grasp, and, as a result, they developed a concern for my shoulder’s well-being.

They took turns keeping me company and quickly learned the language of brain injury, the key monitor numbers to watch for and how to ask for help from the diligent and kind ICU staff. They talked to me, played music, took care of paperwork; this family of action-takers and positive thinkers needed tasks to feel like they were doing something to help with forward motion, as initially actual progress was slow.

Numbers were everything, beyond vital signs: the ICP numbers for brain pressure and the corresponding balance of sedation; my body temperature, which had to be kept a degree cooler to prevent fever in the brain; the electroencephalogram (EEG) to measure possible seizures in the brain. My pain level could only be ascertained by furrows in my brow, which appeared sometimes when I was rotated in the bed, and when Susan told me I would be turning 60 soon (really).

I do not have any memory of feeling pain during those two weeks. At first, when sedation was carefully reduced, I wiggled my toes when asked before the rising ICP numbers required a return to heavy sedation. But as time went by, I stopped responding to these commands despite the nurses’ fiercest attempts [as proven by my bruised toenails]; they would apologize to Susan as they pressed hard on my toenail and fingernail beds, but I did not flinch.

The ICU social workers were the lifeline to my family’s sanity. They scheduled family meetings with the staff and tried their best to include out-of-towners via phone. Early discussions were solely worst-case scenarios, expressing very little hope and only long-term disability outcomes; it was realistic at the time and necessary to hear, but very difficult, especially for my 87-year-old parents. They, in particular, needed to hear some stories of people who had recovered. I am grateful, especially to Dr. Stippler, that that is the story I can offer them now.

I regained consciousness from the coma after two weeks and able to move out of the ICU to a normal hospital room a few days later. My family recounted to me stories about the different songs, dramatic presentations and jokes they had been performing to try and wake me up during the coma. Though I was confused by my predicament, somehow it made sense to me that I was in the hospital, and I felt like I knew that they had been there with me.

They came and went in small-group (or solo) rotation. It was a great relief to learn that everyone was engaged with me in this enormously strange and difficult situation, but each time someone left I needed reassurance that they would return soon. It became my job to recover, but I needed them to be with me, and they came through.

My first few days out of the ICU are fuzzy, probably because of fatigue and the medications I was taking. I remember enjoying small amounts of time with a few visitors and celebrating my 60th birthday in the presence of a cake I was not allowed to eat. (Looking back, I would now say that having my life back was celebration enough!) I tried to be pleasant and cooperative, but inside, I was angry and frightened. I was angry at myself for having ended up in a situation that caused so much suffering for my family. I was angry that I had so little control over my life now, and I was very scared that I would not recover. I also had some strange and intense dreams that left me confused about my reality versus my sleep. The dreams had elements of my hospital life in them, and I still wonder whether they reflected something about what I felt and took in while I was in the coma.

In the main hospital, my case was taken over by a new social worker, who to my pleasant surprise ,was someone I had known for many years. He gave my family the sage advice to move me to a rehabilitation hospital as quickly as possible to get started on therapy. I arrived at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital on March 9, a week earlier than predicted.

This transition, and the subsequent transition from Spaulding to my home, were confusing times because my family were unaware of what kind of needs or what kind of behavior to expect from me. In hindsight, these were two times we should have asked to meet with Dr. Stippler prior to the move to get a better understanding of the care I would need, the difficulties I might encounter and other issues that could arise.

At Spaulding, I was under the care of Seth D. Herman, MD, a physiatrist who visited me daily and gained an understanding of the intensity of my desire to get back to my life, my home and my job. Initially, as I was weaned off the medications and moved into days packed with therapy sessions (occupational therapy (OT), physical therapy (PT), speech and language and group sessions), I became more aware, and my anxiety over my condition and future grew.

I feared that I would not be able to perform my job again; I feared that my new relationship with Josh would end. I cried frequently and fretted that I could not find the woman I was before the accident. I was afraid of being left alone, and even though I knew family members would return in the morning, it was hard to say good night and face the long night alone. My hands shook, and my enlarged tongue was interfering with eating and talking. Exhaustion and a sense of being overwhelmed would come over me with no warning. I was not allowed to move freely in the room; I either sat in an alarmed wheelchair or laid down in an alarmed bed. This added to my sense of helplessness and vulnerability.

But, as at the Deaconess, the staff at Spaulding was kind and patient. I had access to a psychologist to discuss my fears and confusion. Over the next three weeks, I could feel myself improving and releasing some of the fear. I got to know the staff – people who devoted themselves each day to taking care of others’ needs. I knew I was lucky they were taking care of me. I tried to be as accommodating as possible. I went to group breakfasts and therapy sessions and came to enjoy time with other patients and my therapists; being with others helped me feel more normal and less afraid. One night, in a quiet moment, I asked my evening nurse if people really do recover. She said yes, especially the patients who, like me, have support from family and friends. She encouraged me to believe that I was recovering and would continue to do so. Her assurances were so comforting, and I will never forget the peace I felt as I listened to her.

As I worked to relearn basic things, my physical strength, cognitive ability and confidence grew. That seemingly lost woman emerged, and my memory gradually proved to be completely intact. On March 31, I was discharged from Spaulding to go home and continue my therapies as an outpatient. Again, this discharge was one week earlier than Dr. Herman predicted!

I have been home for four months now, and each month has brought me closer to my former self. My energy has come back, and I no longer get overwhelmed and need to nap during the day. I started back to work part time in mid-May and am now able to work full time. A recent CT scan showed that my brain has healed well, but my skull is taking longer, so I have not returned to running yet. I am looking forward to getting back to that, but I have learned to be patient.

I know that the nurse was right that night; it takes support, time and a positive attitude to heal from a brain injury. Practice, eat, exercise and rest. Those have been key for me. I now know to think positively, smile often and believe in the future!

[aans_authors]