“Nihilism stands at the door. Whence comes this uncanniest of guests?”

-Friedrich Neitzsche, c. 1885

Some of my most vivid memories from residency involve the evaluation of neurotrauma patients in the emergency department. As a junior resident, it was one of the few times where I could be integrally involved in a patient’s initial neurosurgical evaluation, the operative intervention and postoperative care. With time I became callous to and weary of the seemingly endless supply of patients with irreparable neurologic injury. A great many of them were simply young patients who had been carelessly having a good time, and equally distressing were the innocent bystanders who, in a devastating moment, had their lives deleteriously altered forever.

Later in my residency career, I entertained the prospect of pursuing a neurotrauma fellowship, but I quickly came to the realization that the prospect of spending a career chasing the effects of secondary injury and “preserving any remaining function” would not be palatable to me. I was not alone in this nihilistic approach to neurotrauma as only eight percent of U.S. neurosurgical residents express an interest in pursuing the field (1). With only this limited work force dedicated to the treatment of traumatic neurologic injury, the challenge of progressing the specialty is evident.

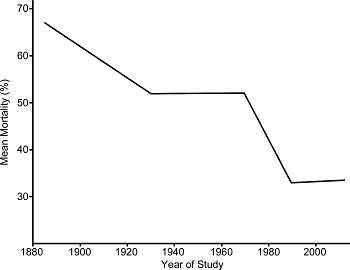

Expenditures in neurotrauma are higher than ever, not only on the financial expenses for inpatients and rehabilitation but also the cost of research (2). Our understanding of traumatic effects to the brain and spinal cord, while still vastly incomplete, is improving at a tremendous pace. Unfortunately, despite this time and effort, clinical results and outcomes remain stagnant and are arguably worsening as seen in TABLE 1 below.

Many studies suggest there is an increasing rate of inpatient mortality in traumatic brain injury (TBI) cases (3,4). We are in desperate need of clinicians who can translate the advances in bench research into clinical results. However, for many of us our experiences with neurotrauma as residents invoke pessimism and skepticism for the future of the field. Eventually, most of us select more lucrative neurosurgical specialties where we can intervene early in the disease process and restore function rather than play a reactive role with limited hopes of repairing damage already incurred. This lack of enthusiasm for traumatic brain and spinal cord injury unfortunately perpetuates a cycle of lackluster results.

For neurosurgeons, the care of a neurotrauma patient requires immediacy and lacks convenience. It can be difficult to maintain any semblance of a regular schedule, and weekends and evenings are rarely spared. This becomes perfectly evident during residency when the exhilaration of an emergency quickly dissipates as a trainee advances in years. Now, as more trauma centers are established due to their increasing profitability, many practicing neurosurgeons are pressed into caring for neurotrauma patients, perhaps bringing a pessimistic mindset established earlier in their careers (5). This lack of passion may be among the many reasons that TBI outcomes are even poorer at lower level trauma centers (6).

With proper guidance, perhaps we can remove the nihilistic approach to neurotrauma from neurosurgical residents and instead instill optimism and hope. Admittedly, this is difficult in the current setting where survival alone is often the bar by which a satisfactory outcome is judged. Without the proper enthusiasm and novel approaches neurotrauma will continue to be relegated to a second-class specialty, and our results will remain mired in mediocrity. Greater emphasis has to be placed on the care of neurotrauma patients in our training programs and at our national meetings, financial reimbursement has to be improved and additional efforts need to be placed in promising trials that can advance the field.

[aans_authors]